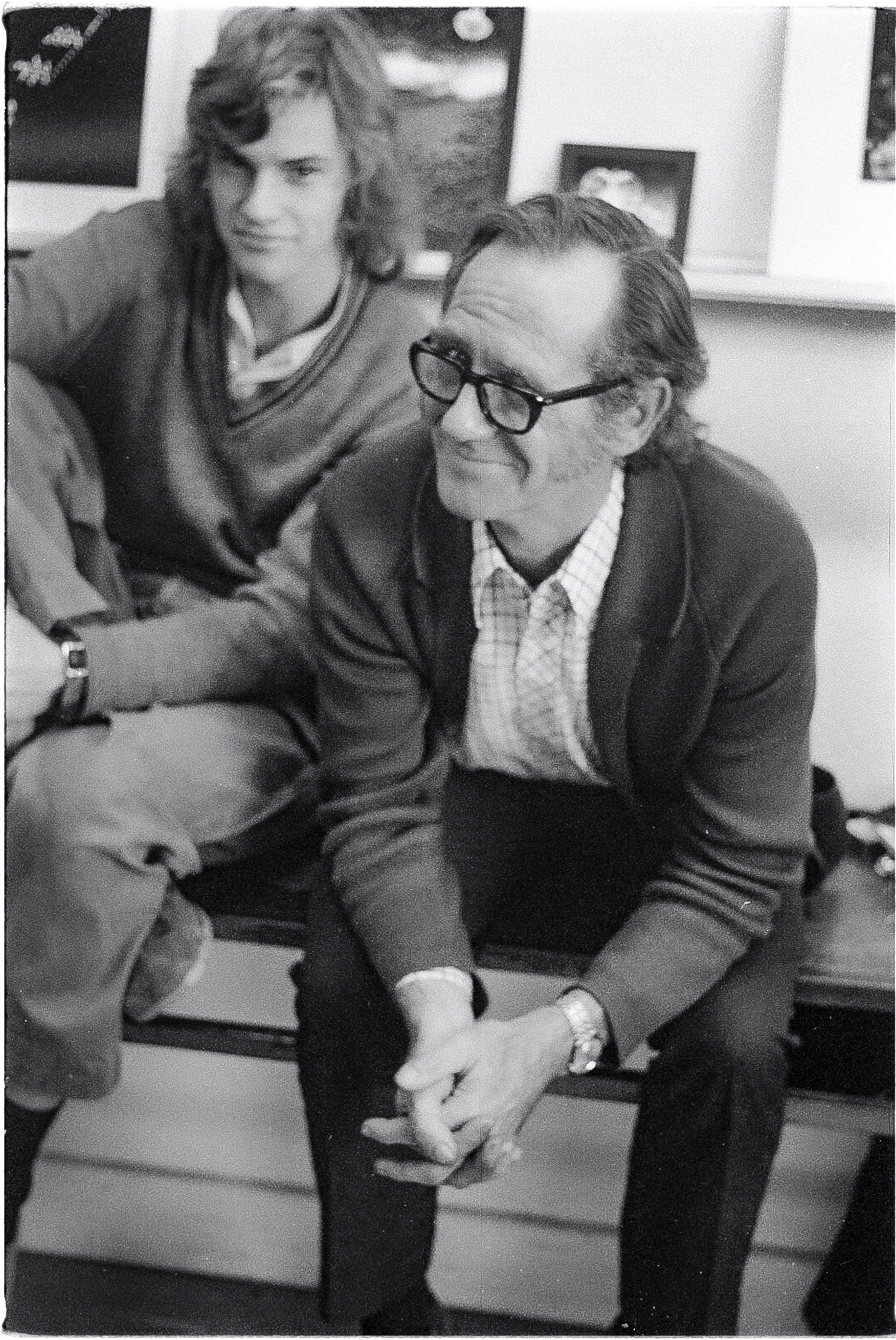

In Colin Abbott‘s Waiting Under Southern Skies Doug Spowart introduces its author:

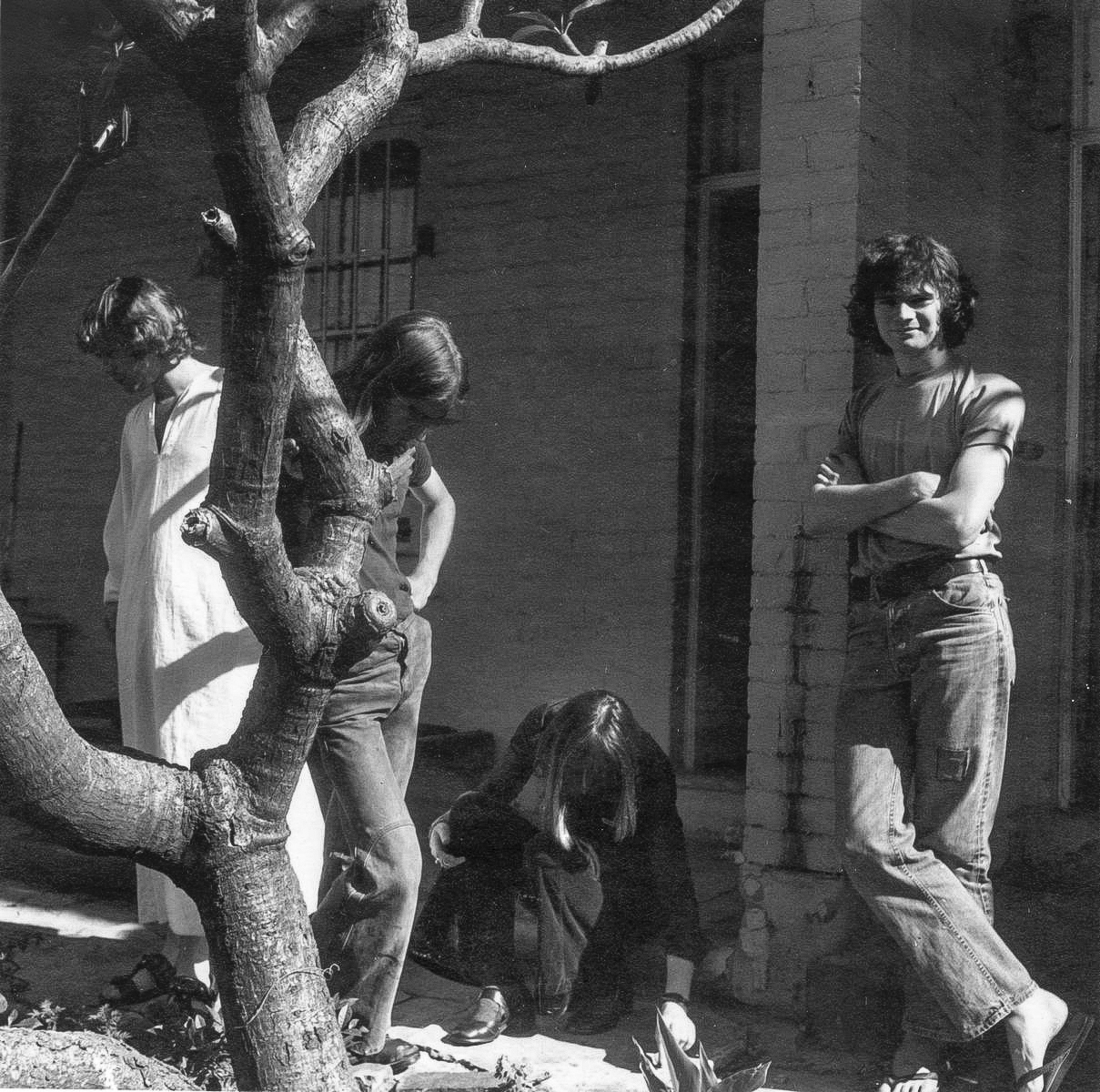

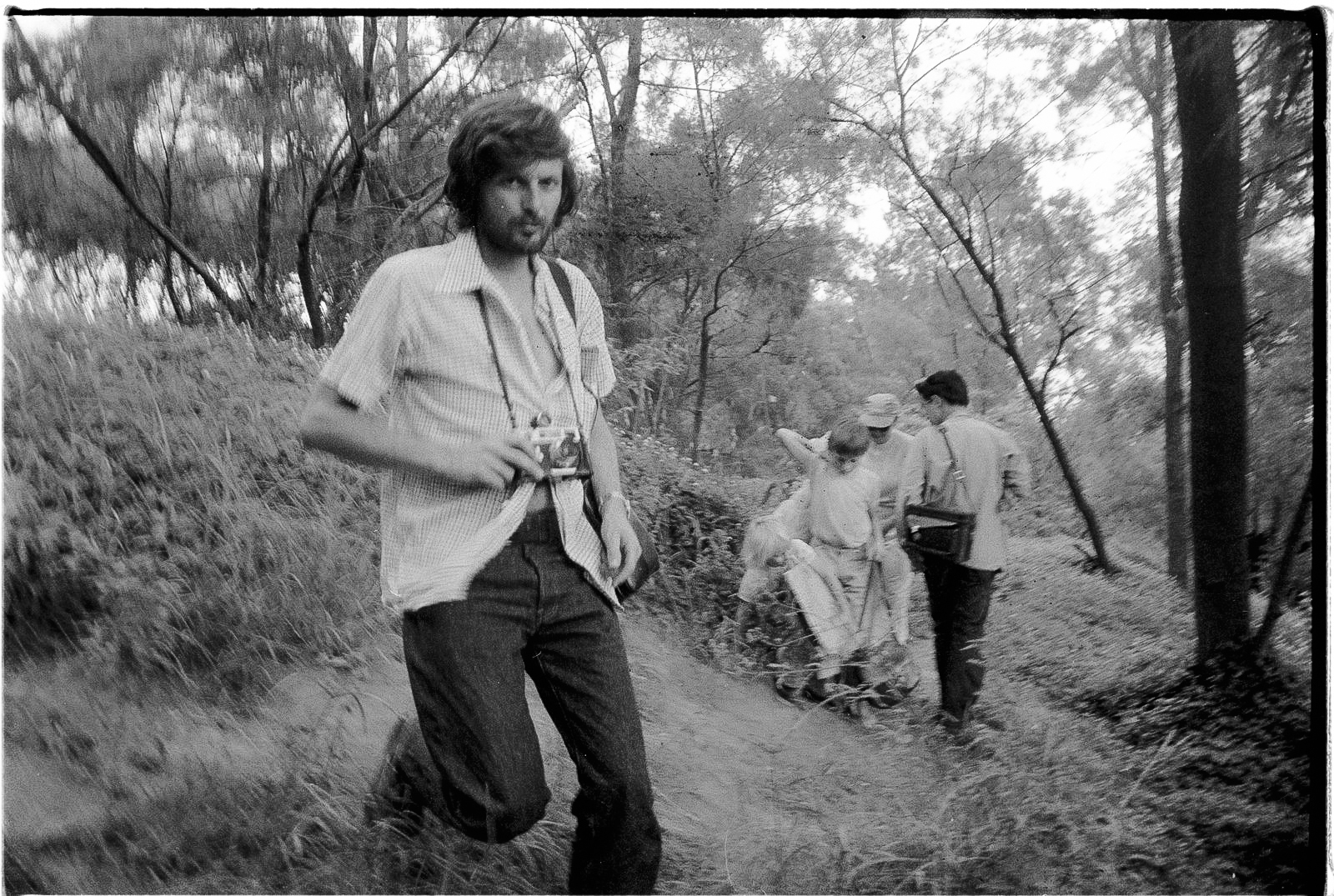

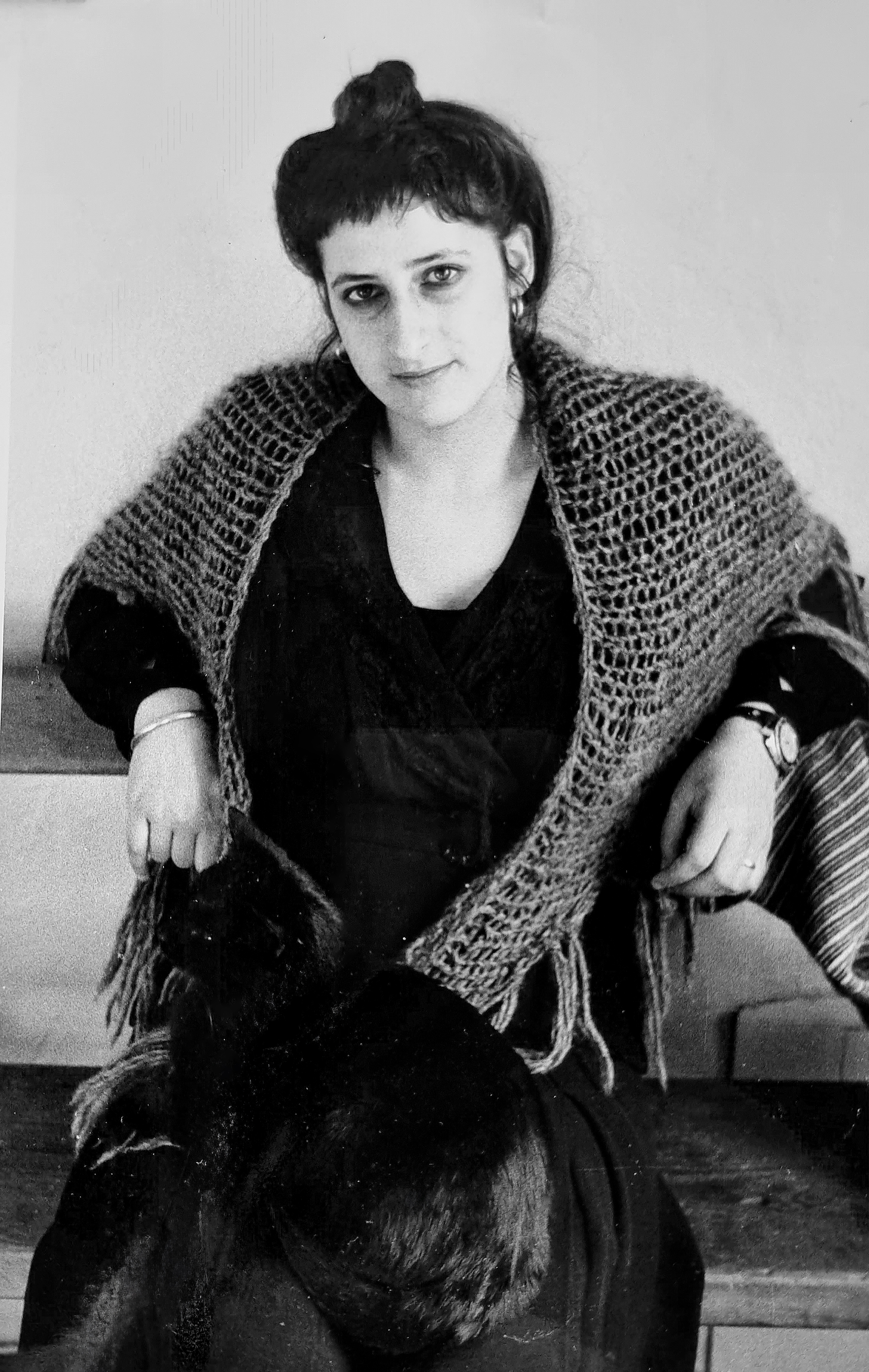

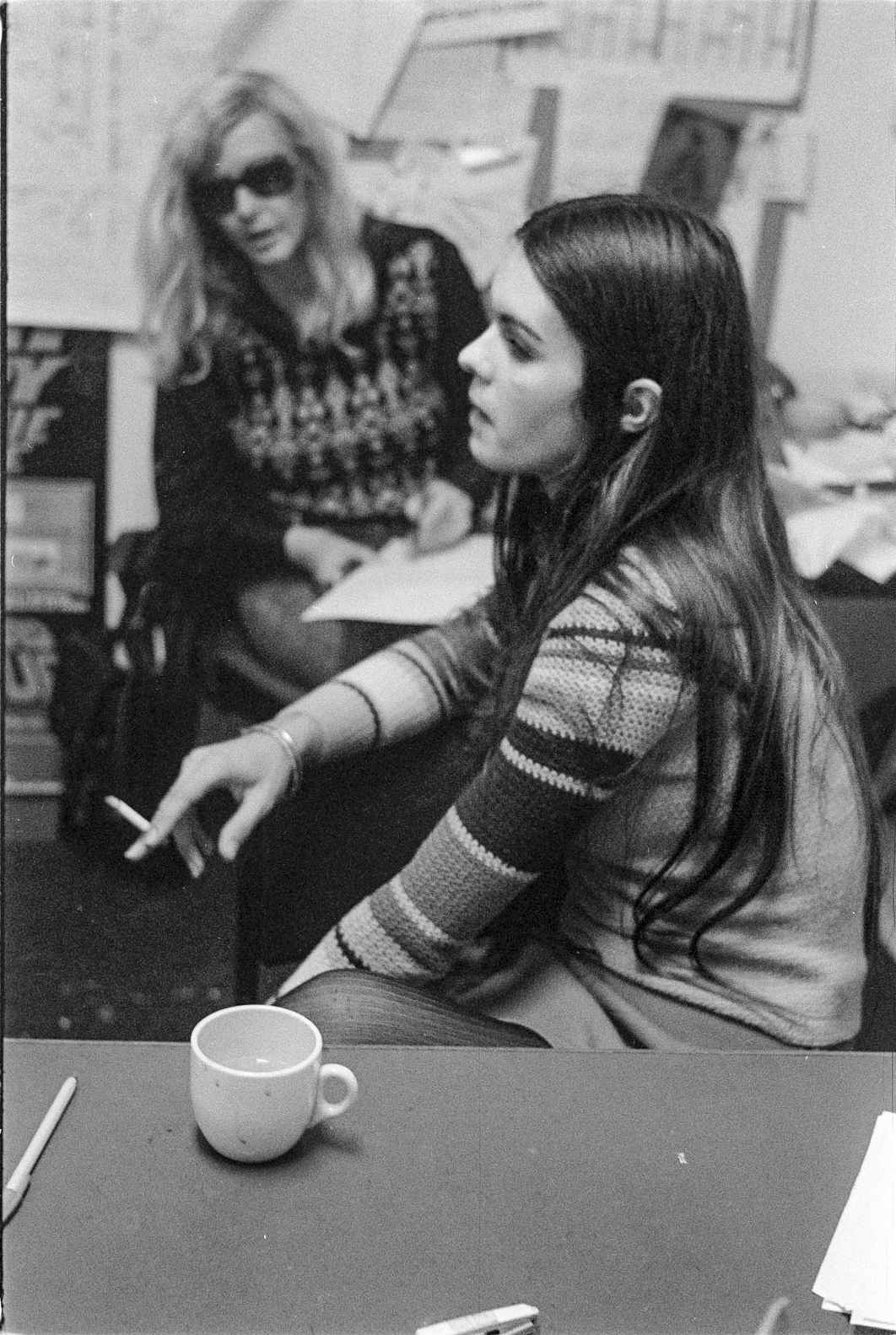

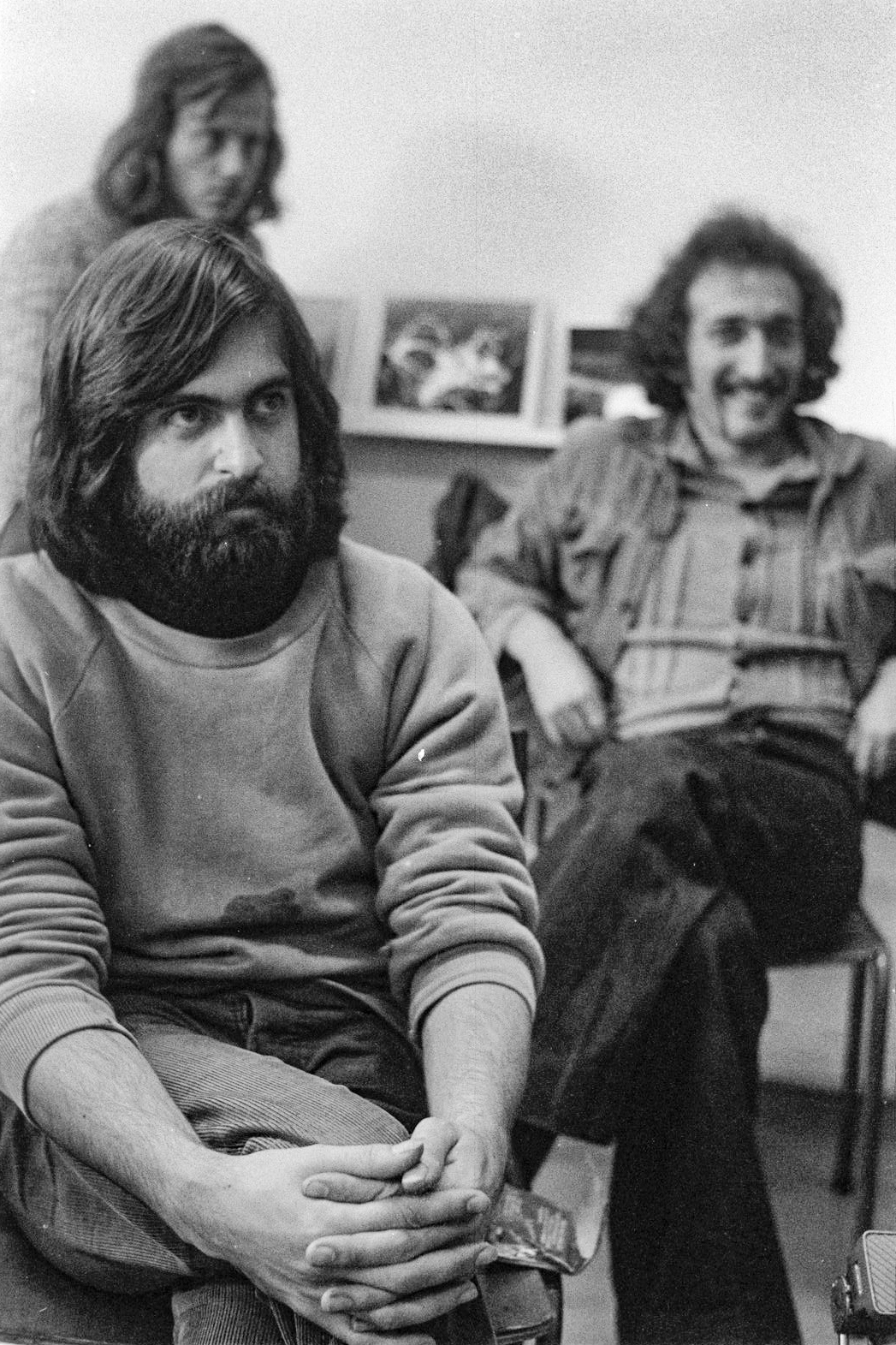

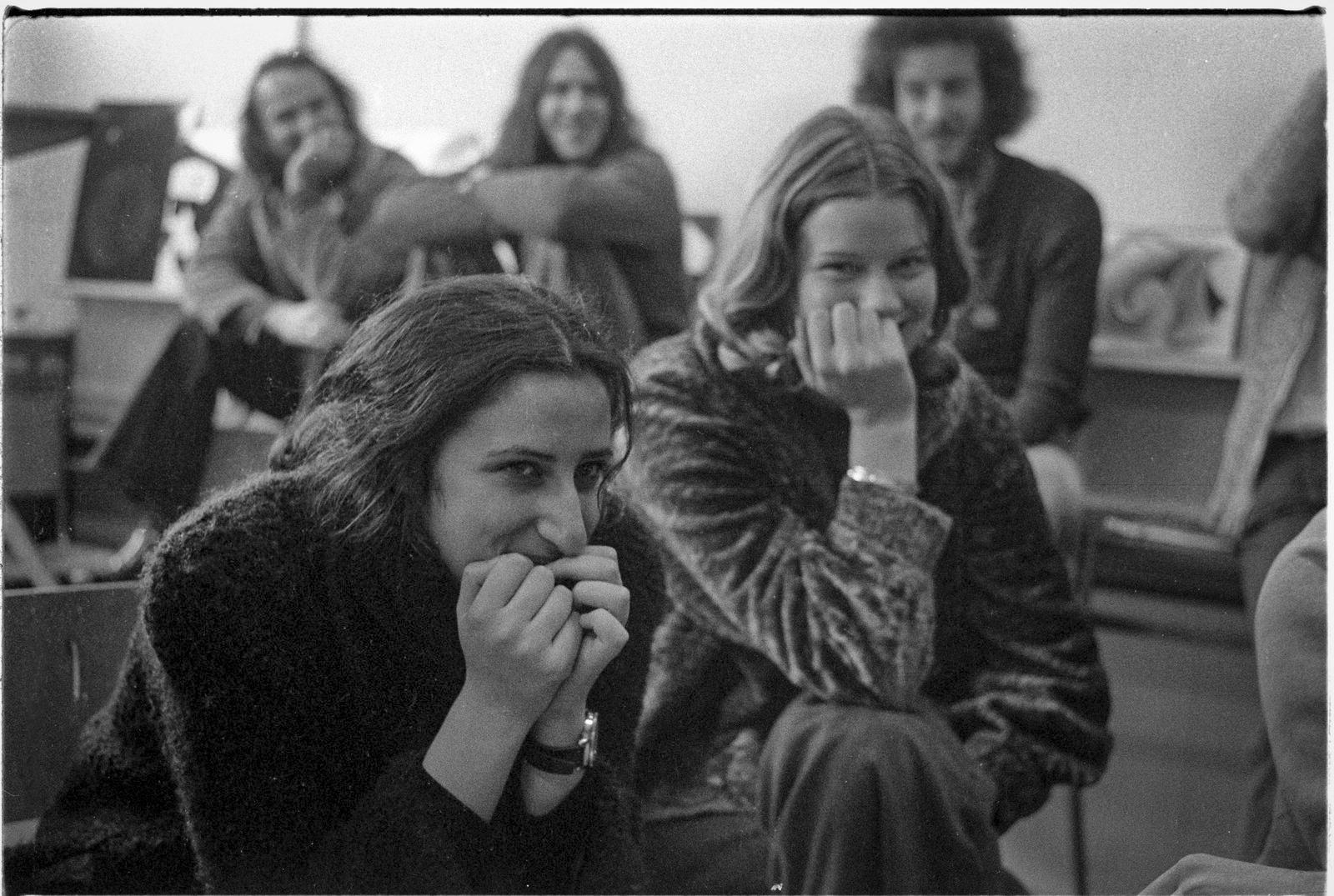

“In early 1970s Sydney, Abbott took up an interest in photography under the mentorship of photographer John Wong, with photographic colleagues including Ian Dodd, Stephen Crowfoot and Rodney Scherer. Between 1974 and 1976 he studied photography at the celebrated Prahran College of Advanced Education during the halcyon era when its teachers included Athol Shmith, John Cato, Paul Cox, Norbert Loeffler and Brian [sic] Gracey. Students of Prahran College became some of the most progressive exponents of documentary and art photography in Australia including photographers Carol Jerrems, Bill Henson and Sue Ford [sic]. Abbott’s co-students also influenced his photographic interests and style.”

James McArdle: I want to discover from you the difference between Sydney photography and Melbourne photography, because you’ve got a bit of experience in both. You started in photography up there, so what sort of a scene was it? You knew quite a few photographers when you started taking photographs yourself. What do you feel is the difference?

Colin Abbott: “I don’t know if it’s a big thing…there’s one significant one; the light that the photographers work with. The light intensity seems to be much stronger in Sydney. And I guess just the weather conditions and so on, it allows people to do different things.”

“I spent 7 years living in Sydney and was involved in photography only for the last 18 months with a little group;John Wong, Stephen Crowfoot, Ian Dodd and a couple of others. We were somewhat isolated from the Sydney scene, not part of any mainstream and though we met others doing things we weren’t closely involved with them. I had only about 18 months in Sydney. Well, I was discovering photography.”

“We saw Jon Rhodes, Anthony Browell, and John Wong was connected with Robert McFarlane and David Moore—he made some contact previously with David, whom I met only once, and briefly. By the time I was starting to produce work, I was heading for Prahran.”

J: When did you consciously start photographing as an artist?

C: [winces] “I’m not a big one for ‘artist’…I’m more about trying to be a photographer with a capital P. It was always my goal to reach that level.

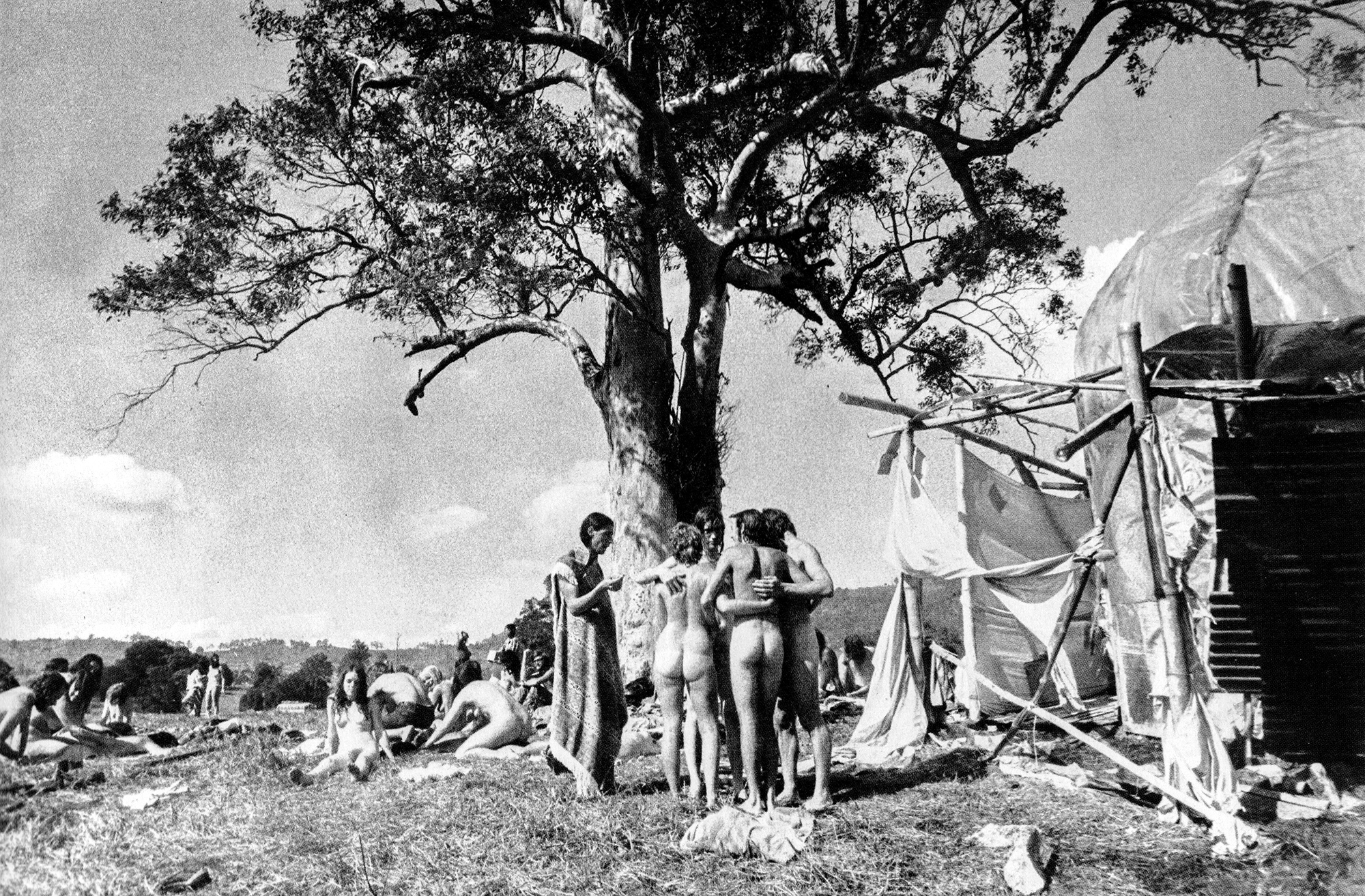

“[This ambition] was probably accidental. We heard the Rolling Stones were coming to Australia and were to do only one interview session, and that was to be in Sydney. My housemate Rodney, who was [at Colin’s ANZAC exhibition] yesterday was a layout artist for the agency responsible for the ticketing and promotion for the tour. He realised that they were producing three different lots of tickets to confuse everybody about where the venue was. Tickets were not to be released until 4:00 on the afternoon it was going to be held, so the journos got no advance warning about where it was going to be. But Rodney came home at 5:00pm knowing where it was going at the old Spaghetti Factory off Oxford Street in Paddington.

“He had a little 50 cc Honda step-thru and I had a little 100 cc Yamaha bike, so we tootled off to go and see the venue. We looked at the front…nothing was happening out there…so we think, ‘we’ll go around the back and have a look’, and at the back is a giant black limousine, and we think ‘yes, they’re here’. Not many people were there. After about ten minutes Mick Jagger came out with Sydney artist Martin Sharp, the Stones’ road manager, and this big black guy who was the security. I took half a dozen photographs, and this one shot transformed the whole thing. That was genuinely the spark that suddenly said, ‘well maybe I can do something with this’.

J: So did you see yourself as a paparazzi photographer, or a photojournalist?

C: “I think if I had any ambition, it was to become a LIFE photographer. But of course, LIFE magazine died in 1972 and they only did annuals after that…so the career prospects were not looking great…National Geographic maybe…so it was vague. My previous tertiary experience didn’t work out…I’d abandoned having a piece of paper and was prepared to chance my arm with the confidence that I would find something…it’s hard to work out when you’re a young person…but find something that you have a passion for, that you love doing. That is the real key to personal success, the comfort of living in your own skin, feeling that this is what I can genuinely do. It’s like a medium in that it’s something in which you can swim and find yourself.

“That episode was what gave me that. Of course my friends in Sydney thought it quite strange for me to enrol at an Art school, especially in Melbourne in a suburb with an unpronounceable name, saying, ‘oh, you’re mad…’, in a way that was sort of supportive, but at the same time they were thinking, ‘I don’t know that this is going to be in your best interests.’”

J:…and of course, it wasn’t [laughs]

C: “Oh, no…well sort of..yes and no! To say 50 years later that what I did do was worth doing, is gratifying. At Prahran I benefitted most from the age diversity of fellow students; the youth with energy and desire to learn, and older ones with experience and knowledge, that was a catalyst.”

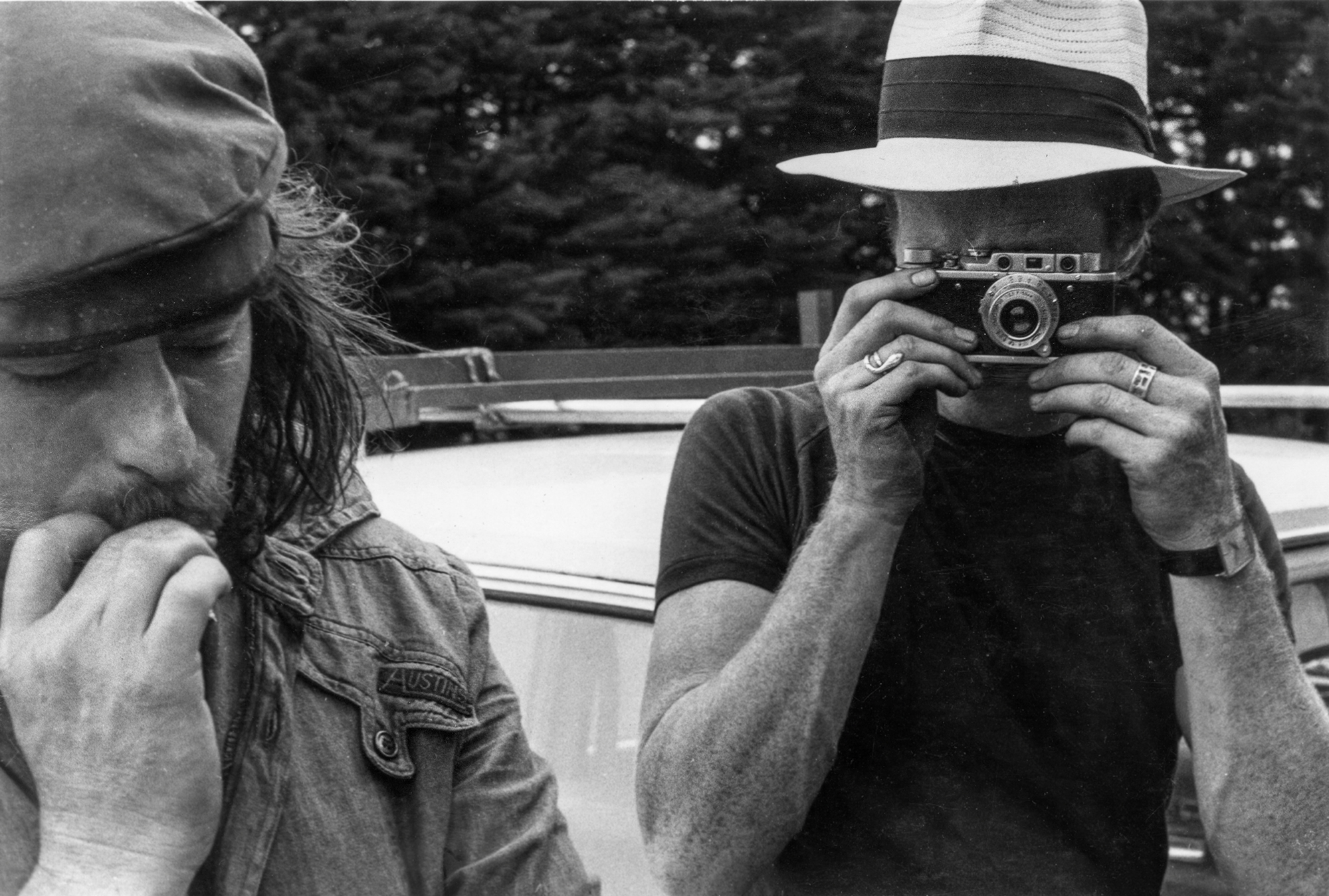

Photojournalist Andrew Chapman remembers Colin as “a fellow traveller…having lived in Sydney with a group of documentary photographers. He carried a Leica and was keen on unobtrusive street photography,” and it is from Colin’s archive that we have so many images of the students of the mid-1970s.

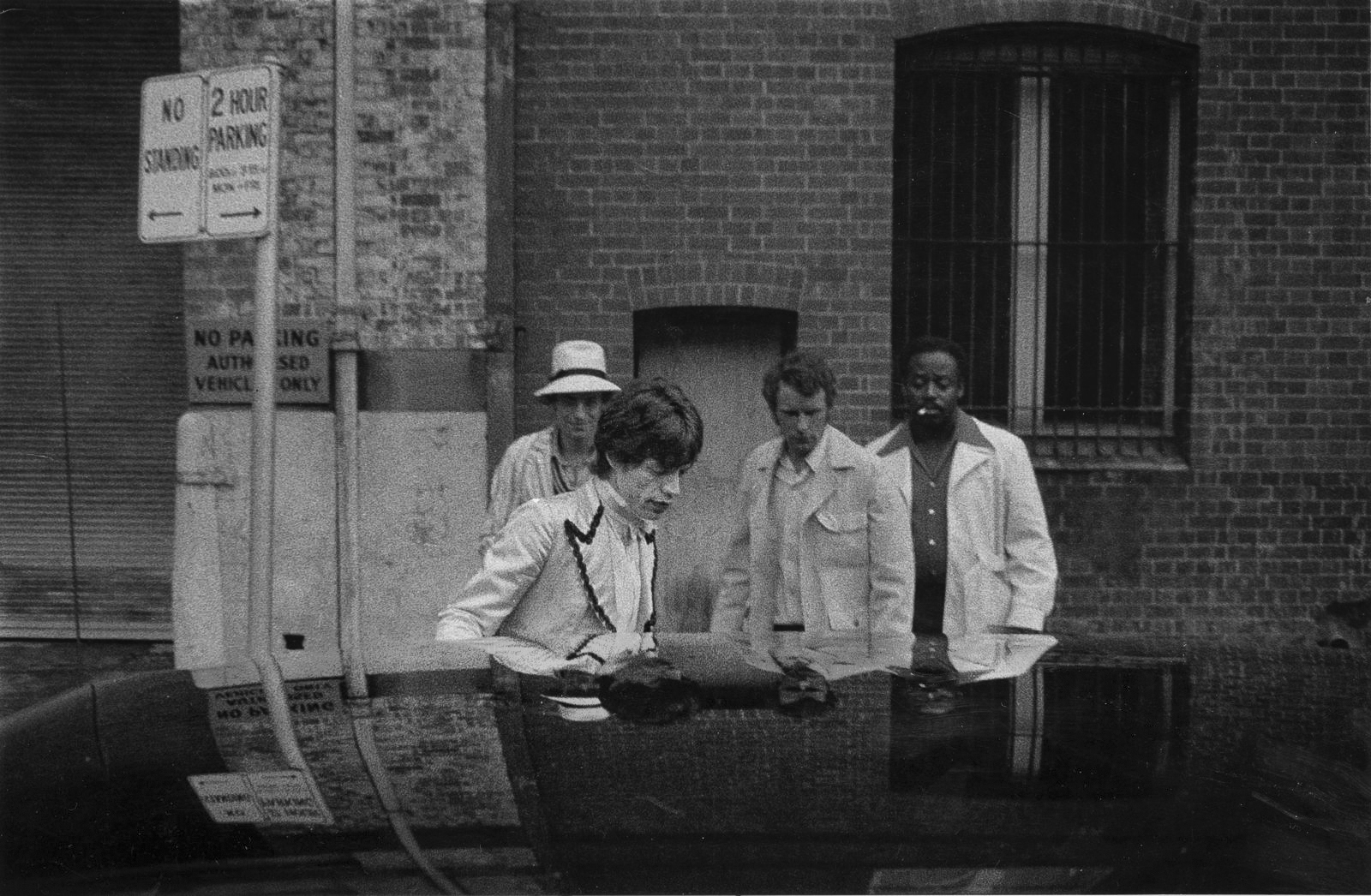

Colin’s is a rare series of photographs of Prahran College Union director Jean McLean, whose energetic, positive influence over 1974–1980 we valued. Convenor in 1965 of the Save our Sons Movement, she campaigned against conscription and Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War that we hated as vice-chair of the Vietnam Moratorium Movement, clashing with the law as one the ‘Fairlea Five’ jailed in Women’s Prison for trespass when handing out leaflets. In 1974 tertiary fees were abolished, opening up educational opportunities for student colleagues from working class northern suburban backgrounds and mature-age students. Students Euan McGillivray, Warren Townsend and Maurice Hambur taught in community courses set up by McLean.

C: “I came back to Victoria knowing nobody, except my sister and brother-in-law so it was a bit challenging on that front, but meeting yourself and Andrew, and the other classmates was like going home and there was always work to do.

“It was a good bunch, wasn’t it, and people fitted in pretty well…you could blend in with whoever you wanted. A couple of loners involved, yes. Well, Bill Henson was one, Robert Cartmel and John Sara and some…Ray Saunders and Faye Williams, I don’t know what happened to them, but I think we all found different pathways in life.”

“When we organised the 2014 exhibition Prahran 40, we found that out of the 20 who started in ’74, about 16 had pursued some photographic career…commercial photography or, like Andrew, in newspapers and magazines or others like yourself, going into academic areas teaching photography. So most people found a pathway, and for me, it gave me the knowledge and experience when I was organising the family business [Bosistos eucalyptus products], in advertising and promotion, so that I had an understanding of the photographic side and creative thinking. That’s underestimated in students’ development but companies pay big dollars for today for people who can think creatively, not just to identify problems but to come up with solutions— it’s part of the future.”

J: I’m giving a talk at the Castlemaine Art Museum around a subject ‘photography comes to the art school’. Art is a dimension into which photography has moved…that is if you define artists as being people who exhibit, just as much as singers are people who have fans and audiences. So the subject matter might not matter, but it’s really that artistic impulse with which you make a career of your medium, and you’ve got something to say and a particular angle on things. Now, I look at your picture of the dog and the tree.

C: “Oh, right. Yes. Pasha…”

J: Pasha…so tell us about taking that photograph. It appears to be a slightly underexposed negative, because the dog has no shadow details, it’s just a silhouette. The tree in the background is similarly a silhouette, but you’ve got the texture of the pale clouds and rock. It’s just one fleeting moment and the dog’s going to walk out of the frame any second.

C: “It’s, I think, in the Brisbane ranges past the You Yangs, where I’d gone there to take the dog for a run in the countryside. Those days I tended to wear the camera quite regularly, at the ready. Obviously, what the dog was doing I don’t have clear recollection of now, but I’ve always loved the picture, just for the graphic quality. Probably should have done a little bit more with setting the f stop but it gives a graphic quality…it’s the realism, it’s a real photograph. I’ve always liked Walker Evans’ dictum that a photograph has to be transformative if you want it recognised as a proper photograph, otherwise it’s just a picture. We can’t always succeed in the transformative part but we can try. From John and the other lecturers I learned that you get lucky accidents to which you have to be responsive…to anticipate something is going to happen, ready to push the shutter as it was back then…it’s a ‘seventies image on film, so it’s it’s out of that era.”

J: Tell us how you printed it.

C: I’m not even sure where that was printed.

J: Really?

C: “I never had a proper home darkroom…oh, in Sydney we had this big terrace house and it had the standard laundry space that they had in those days, so, John, a couple of us, we just converted the laundry and bathroom to a darkroom. My early work from Sydney was all printed there. When I came to Melbourne, fortunately, Andrew Chapman had a home darkroom, so I did printed there. When I lived in Holden Street with Andrew, Heather, and Leonie Ryan from the ceramics department—Andrew’s first girlfriend before Josie—we had a darkroom, so I suspect this picture was done in there. I didn’t take enough advantage of that; when I got this house, I had no space for a darkroom; too many kids, too many other things got in the way of printing.”

J: What about the type or grade of paper, or is it multigrade?

C: “In Sydney we were printing on grade one probably most of the time, using Ilford films developing in Rodinal and standard Ilford Bromophen. The light there gave you the intense shadows. It took me a little bit to realise that in Melbourne you needed to switch to a grade two. Jean-Marc (Le Pechoux) over in Armadale at the Lighthouse darkroom showed me a couple of other little tricks, by adding a bit of Kodak D76 [film developer] to your paper developer to give it a bit more strength in the blacks…there was a bit of an art to it.

C: “In Sydney we were printing on grade one probably most of the time, using Ilford films developing in Rodinal and standard Ilford Bromophen. The light there gave you the intense shadows. It took me a little bit to realise that in Melbourne you needed to switch to a grade two. Jean-Marc (Le Pechoux) over in Armadale at the Lighthouse darkroom showed me a couple of other little tricks, by adding a bit of Kodak D76 [film developer] to your paper developer to give it a bit more strength in the blacks…there was a bit of an art to it.

“Had I met Michael Silver back then, his knowledge would have been really useful. I got reasonable results in Sydney then plateaued a bit here; there wasn’t a staff member [at Prahran] who would become your best buddy to really advance your technique. Unfortunately Derrick and co didn’t quite come up to it. Maybe I come out of the purist school, like Max Dupain; I’m just reading in a book about how he’s been the orthodox…and David Moore and then John Wong…I come out of a very orthodox purist [group]; full frame…if you can’t do that, don’t bother…you’ve got to be close enough; imprinted in my brain was this whole dogma. They were guidelines that would help you produce what would be usable, if nothing else.

“But there wasn’t a lot of encouragement to be an art photographer out of that group…though that’s where they were headed. But I wasn’t, not quite.”

J: Well what about John Cato’s landscape?

C: “Yes, I did have a lot of regard for John. Looking back, I feel he was the closest [to being an art photographer].”

“We were in such a modern phase, transitioning from the old days to the new, but …none of the lecturers there had any regard for the music of the ’60s and ’70s; no Hendrix, no Stones, not even the Beatles. Oh, you’ve got to listen to all this old crap that was their go-to.”

I came out of a family that hadn’t any of that… my mum was listening to jazz and some of the more popular kinds of music. We weren’t a big music household. So for me it was the music of the ’60s; the Beatles onwards; the Stones and the English rock revolution; and the blues; I didn’t quite fit with their thinking.

J: Paul Cox’s, Nepal series book came out in 1970, and that photograph of yours of the dog works on that same low key scale from a slightly underexposed negative that pulled out the highlights and kept the blacks. Paul Cox’s series in Nepal relies on that …

C: “Yes, that’s the difference with someone who’s in charge of technique. You were taught to bracket your exposures, but you can’t in that situation, so sometimes you do get one that gives a different impression when you print…a different light. Like Elliot Erwitt, I’ve always had a soft spot for a dog in my photographs.”

J: But at the same time, it’s not a humorous photograph.

C: “No, no, I haven’t set out to use the dog as the the butt of a joke…”

J: To me, it’s almost, Drysdalesque

C: “I like it because it’s different and it’s informative; it tells you about the dog. Yes, he was a mad character. I got him through a friend. He was going to be put down. I had the gun held to my head—it was ‘you or the dog!’ so I took him. I was living in Rathdowne Street with a couple who also had a dog, and they were good mates, the dogs. Then one day, he disappeared and we couldn’t find him. Nine months later, when there’d been an explosion in a car yard down near Collingwood, I went there and I saw him; he’d made friends with the kids in the flats in North Carlton opposite the swimming pool. They were calling, ‘Racer, Racer’—they’d given him a name — and he was a rocket. We took him back, and the woman we shared the house with eventually took him on; we couldn’t have him in Holden Street because one wag of his tail would dispatch Leonie’s ceramics. He didn’t last long there and, I think ultimately, unfortunately, with liver cancer, he passed away…that life on the streets wouldn’t have done him any good…”

J: So there’s a subject in that image that is significant to you and it makes that environment a setting. I’m sorry to be harping on about that picture, but it has it has, that kind of surreal quality to it, kind of oddness to it, not necessarily purely surreal.

C: “Some of our little group in Sydney had a focus, when I first started, on ‘strange pictures’, humorous, weird angles on things, so I suppose it comes out of that. You might say ‘that’s no good, just forget it’, and it would be still be living on a proof-sheet, except that you see something in it. I liked it, and it captured that dog, which is a personal tale for me…you think of Hanging Rock, the sort of mystique around all of those hills and mountains, it’s that kind of element, a stark landscape, mysterious.”

J: …and I have just seen your Anzac, exhibition, my very favourite there being the Simpson and his Donkey actor.

C: “Well that’s right, and again, it just unfolds in front of you and ‘click’ you’ve got the lot. It’s Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’, to which I try to add…if I can…other elements. It’s a representation of Simpson and his donkey (though I don’t think he had a white donkey).”

J: Or indeed, if Simpson existed…what was his name?

C: “Kirkpatrick. Yes, there was a person doing that, who only survived there for three weeks and achieved this mythic status…helping your mates, it’s mind-blowing.”

J: It’s almost a religious procession…

C: “That is in there, but what excited me was that I caught that old man moving against the action in the middle of the picture. Each element adds its own component, and the beauty of seeing them [printed] up so big is that you can actually see the detail.”

J: There’s a young cadet on the side with a bandage over his nose and you might not see that on an 8×10 print. At a big scale it’s epic.

C: “That’s right. And the myth has become epic in its own right. It was inculcated into all of us as symbolic of the mateship, to rescue guys from no-mans-land to bring them down to the waterfront to be evacuated….under Turkish fire it would have been hell, yes. And other blokes did it, it wasn’t just him; he became the symbol of it in a story picked up on by a journalist and bingo..it’s ‘bigger than Ben Hur.’”

J: So, in looking back at that photograph and deciding, oh, that’s going to be a big image in the exhibition, obviously it had a lot of meaning for you. It has so many elements in it…the church backdrop which makes it almost a quasi-religious procession…something out of Eugene Smith’s Spanish Village. You may have channelled that…

C: “…a bit hard to do on Flinders and Swanston!”

J: But it’s the awareness, a heightened awareness that photography brings.

C: “Yes. It means that you do see those moments. I’ve tried to continue that in my contemporary documentation of ANZAC Day. The march has become more multicultural—or had been up until recently—the Vietnamese people were marching and the Greeks and the Italians and even the Chinese were getting involved because they never had their families represented even though they too were fighting World War Two. I was capturing that, but as with all events in the CBD, security became the priority and it is harder to get a press pass, then even when you have one, you are locked in and can’t move around to get different perspective.

“In those earlier days you could walk in and out of the march, interact with it and respond to how you felt. It was easier because the veterans were used to being photographed; it was a source of pride and you might end up in the newspaper, a little egoism, or they wanted a photo with mates they might not see in a while; great training for young photographers because they’re not going to be shooed away. There’s not this current anxiety about being photographed for some malevolent purpose.

“I always wanted the work to go into the public domain and to let it live on. It’s a piece of history. If they’re interesting photographs to look at as well, that’s a bonus. I tried not to just focus on the military, but it’s a bit hard to avoid. That work was never seen by a lecturer, you know and I don’t know that they would have taken any notice of it.”

J: Well, I remember an ANZAC assignment being set but you don’t…

C: “No, I don’t recall it; I might have missed the odd thing as I couldn’t get the educational allowance due to having done a year of university paid by my parents, so my course was disrupted by having to work, but I don’t think I missed that much.

Prior to his Anzac show, Colin has had several exhibitions since 2009 including Enigma with Photonet Gallery; Out There at Manning Clark House, Canberra, 2013; and a photo exhibition celebrating the 150th Anniversary ofPrahran Market, 2014; then worked with Michael Silver for Magnet Galleries for exhibitions on 70’s Melbourne (2017) and 80’s Melbourne (2018).

J: So when did you first take a photograph? When was your earliest photograph?…as a child, or…?

C: “As a child? There’s a picture of me with my parents at, Kai Tak airport in Hong Kong when my sisters and I were flying back to Australia for boarding school in February 1966. I had the family’s old box brownie round my neck so I took some then. Later they disappeared.”

J: Okay. Is there a first photograph for you in your history, that you can identify?

C: “In the modern sense, since 1972? Sitting in a box somewhere— I’ve seen it recently—I’ve got a couple of small prints, one of a dandelion and a couple of other little things from my first roll of film.”

J: Was there a photography club at school?

C: “The first time I saw an image being printed was at my boarding school where they had a little darkroom, but I didn’t actually get involved because I didn’t have a camera. Seeing a blank piece of paper transform into an image… that’s magic, but I only did my own processing when when Rodney and I moved to Surry Hills where John Wong lived. Rodney and I shared a house in Enmore with Mimmo and a Melbourne couple Nancy Adair, a member of the Adair homewares business family, and her then boyfriend Rex. She was studying to be a film editor and was a friend of Gillian Armstrong. Both were around 21, but Gillian looked so young that bus conductors would sell her a child ticket; she wouldn’t complain. She was drop-dead gorgeous and already on the way to being a filmmaker. She was part of the the 1971 first Sydney Film Festival, I think. I went along for a couple of days and that enlightening for me, having had no art connection but who liked film; to see that was extraordinary. Through her I became interested in film and filmmaking. Then progressed to photography.”

J: Did you go to the St Kilda film festivals.

C: “No, I’m not a film buff, but in Sydney I’d go and see Bergman, Fellini, and other really great filmmakers at one of the unis’ [film clubs], relatively cheaply, to appreciate the masters. I saw Akira Kurosawa’s work and he became my favourite.”

J: Do you think that’s rubbed off on your photography?

C: “A little bit, a little bit—his beautiful way of seeing things is classic, and he has the capacity to make a Tokyo-based film, then a movie based on historical drama like Seven Samurai, then make a gangster yakuza story set in Tokyo; contemporary stories followed by historical dramas. An amazing career…and then the colour work. Epic.”

J: You’ve collected a lot of photography books and maybe you’re a bit of a photography buff, if you admit it…

C: “Look, I’ve got a few, but I don’t have a very extensive library there.”

J: But you enjoy looking through photographs…

C: “That was part of my education when I was just starting to learn, reading through those seventeen LIFE how-to-photograph books. The various secondhand photography shops in Sydney at the Central Railway end of Elizabeth Street and Pitt Street presented the opportunity to pick up a bargain.”

J: So you got yourself a Leica?

C: “Well, that was through John [Wong] and his connections, to get the right tools for the job; a worthwhile exercise. But jeez they were heavy these days, you really notice the weight in an M3…no wonder I had to have a neck operation…my little Lumix is so light.”

J: How do you feel about the switch to digital. How do you cope with that in your own work?

C: “Well, unfortunately my cameras, and all I’d shot during the Merri Creek power line dispute, was stolen. It put a rather abrupt stop to my photography.”

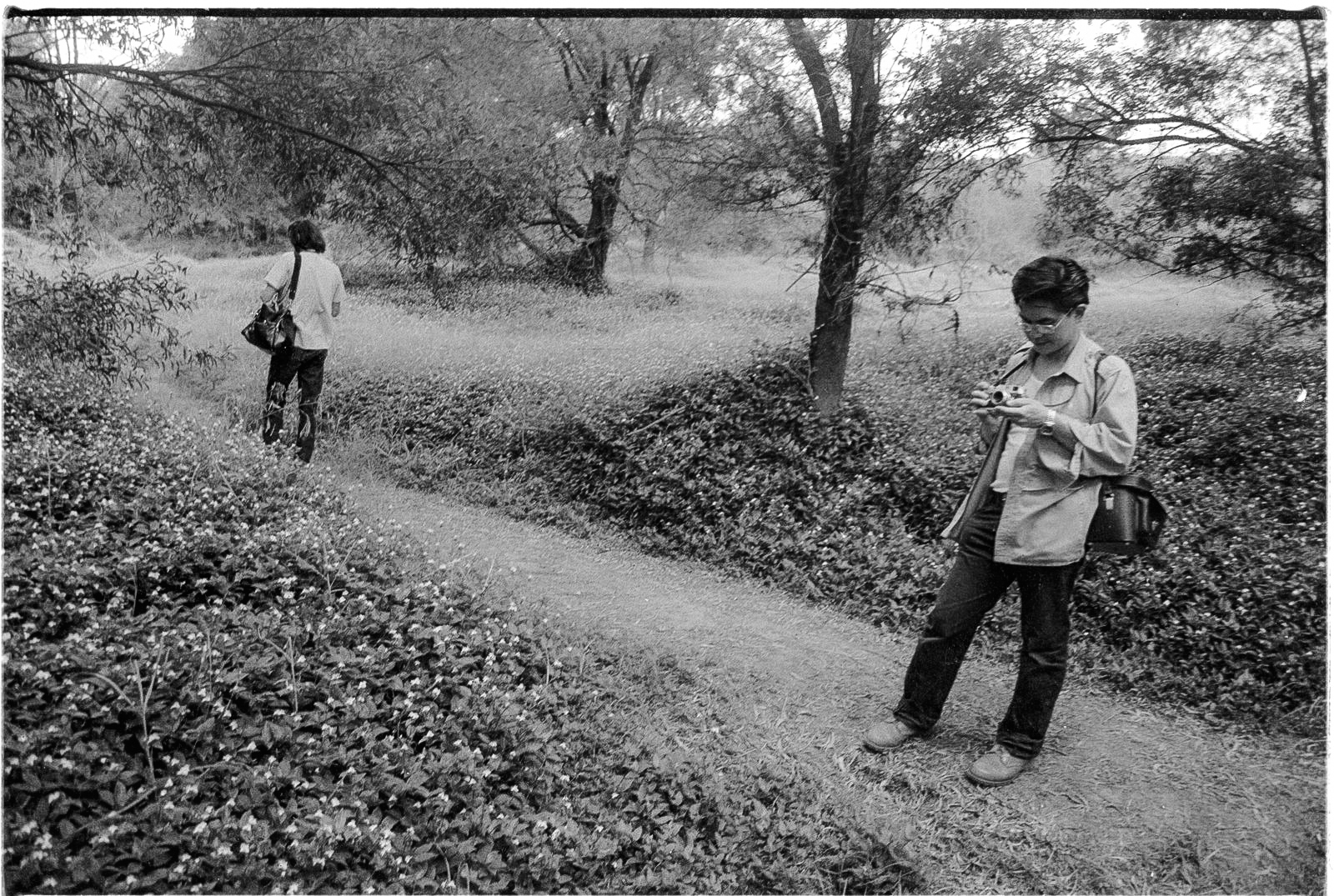

Colin Abbott and his family moved into North Fitzroy in October 1982 and soon encountered a dispute at the end of Ida Street; the Ministry of Housing wanted to build houses on land previously reserved for a canceled freeway, but residents, including Colin, wanted to preserve the Merri Creek environment. Residents took the Ministry to VCAT and won half the site, which the City of Brunswick then had to buy to preserve it. This victory led to a broader effort to preserve land areas and rehabilitate tip sites along the creek. The State Electricity Commission (SEC) later decided to run lines on poles from the Brunswick Terminal Station to Richmond, prompting community concerns about radiation and environmental impact. A major protest resulted in nine arrests and a commission held by the Cain government which concluded the lines could be placed underground. Incidentally OLEX Cables had developed a new cable suitable for the purpose. The Creek became the only inner-city waterway without visible powerlines, and enhanced open space for residents.

Colin, inspired by Eugene Smith’s Minamata work, actively participated in the protests. The neighborhood, still working-class with some industrial activity, was predominantly owned by Greek and Italian migrants. The previous owners of Colin’s house, an Italian couple, were moving to a better house in Templestowe as their current one was deteriorating.

C: “In the 1980s it was still a working class kind of suburb…there was a printing factory down the end of our street, industry and manoeuvred its way in. There were drug addicts in the area. Coming home late from a meeting of the Creek group, I found I had forgotten to take my cameras out of the car, and the boot was easy to pry open. That was at the end of my Leica, my Rolleiflex and my Pentax as well, and about six rolls of film documenting of the whole project. All I’ve got is an image of Councilor Millman, Mayor of Fitzroy in his mayoral robes. It’s not the best photo, just nostalgia.

“After that I was working for my dad, driving to Moorabbin, and life became focused on work and the kids. The boys were getting older and life changed without free time to do things that I used to do. I was taking family pictures, but I didn’t get the… and the amount of money we had to put into this place to resurrect it meant we didn’t have spare cash to indulge…it just didn’t happen, and I didn’t get a Leica back. I still had the old IIIF but it was getting too old; it had done its job. There were family commitments 200km away in Western Victoria with Heather’s parents. Her dad passed away in 1988 after a long illness, and then her mother in 1998, unexpectedly. Life was busy with those things and I had no clear photographic direction.

“The state doesn’t have a proper photographic museum with large-scale facilities that it should have. In 2007 I spent time with Michael and Suzanne who had set up the forerunner of MAGNET in Fairfield . It was ten minutes from here and that became my photographic connection.”

J: So how did the idea of a Prahran exhibition come up with them?

C:” I think I had the idea and encouraged Michael and Suzanne and Andrew to take it on. Michael had seen Andrew through his medical crises and was his closest mate for that. They were prepared to have the show at their New North Gallery in Fairfield. We rounded up the alumni and pulled it together. Andrew and Julie had done a lot with the MAP group and Michael had been involved with that project, so there was the nucleus to make it work. We made it simple; each exhibitor showed one old photo and one contemporary. We were working with one year level about 25 people, enough to make it worthwhile, though Phil Quirk and a couple of others were ring-ins from other years.”

J: And you managed to get in touch with Derrick Lee and his archives?

C: “Yes and Michael got the class list for the results.”

J: Yes, and a few comments…!

C: “Yes…not sure I wanted that promoted. No, but still, a valuable exhibition.”

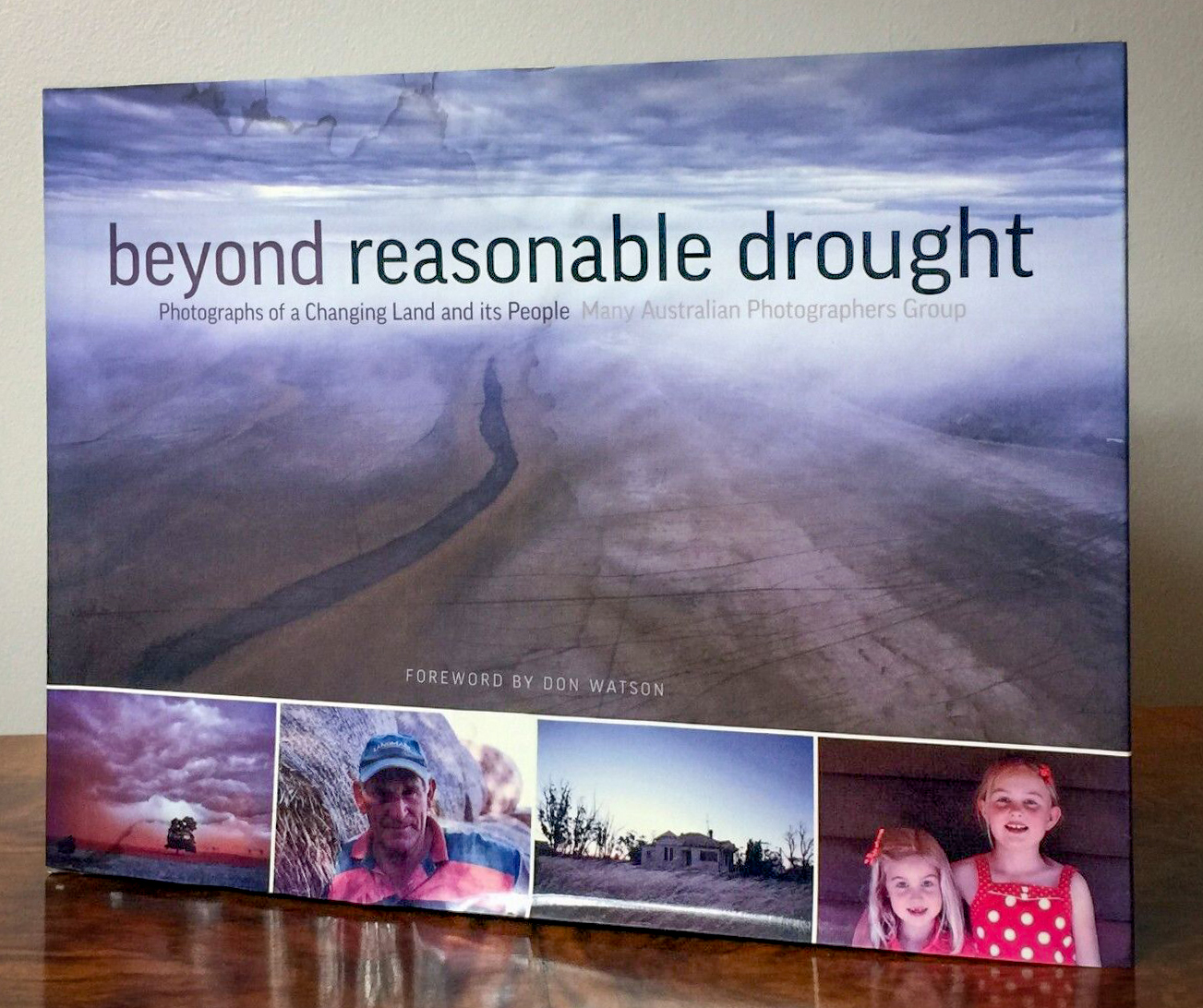

J: And they had also had the Group M exhibition there.

C: “Exactly. That was part of it, seeing that little collectives of photographers can actually do decisive things which become important in the history of photography, as the MAP group has. The collective approach was the strength of their book that will tell the story of that drought and, effectively, all droughts. It’s an Australian version of the photographs of the Farm Securities Administration, a different storytelling, but the images are as important as a benchmark of climate change. I wasn’t involved until they actually wanted to become a proper registered association; I helped with some of that.”

J: Your other involvement with photography organisations is, Light Vision.

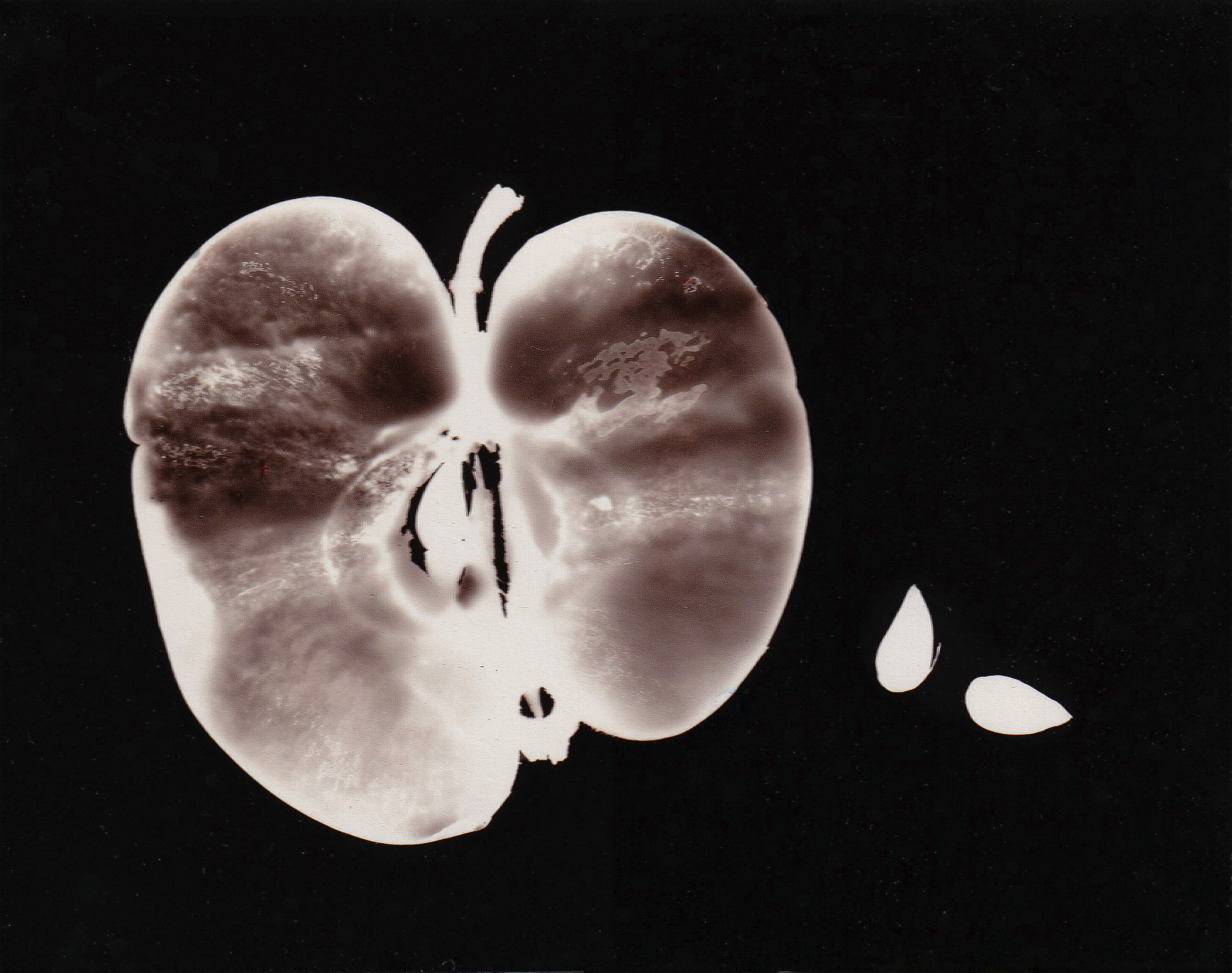

C: “Yes with Jean-Marc, we were going to somehow emulate Camera Work with our photogravure press. I somehow found out about a press that was in the city, in a back lane where Melbourne Central is now. It had become built out. It weighed nearly two tonnes. We had to have a big crane and could only lift it out on a Saturday, and only with a permit to drive a truck in. We had one crane and a truck to drop it on, then another to take it off in the little back lane where Lighthouse Darkroom was in Armadale.”

J: So who financed all that?

J: So who financed all that?

C: “Me.”

J: So you have been a benefactor of photography for some time!?

C: “A few Photogravure Coop members chipped in, but basically it was me, attempting something beyond my capabilities, a terrific project; well, it would have been. Unfortunately, Peter Graham, who was to teach us to operate the press and etch the copper plates—died of a heart attack, so we lost the knowledge base. We had a good go at it; Jean-Marc got the press to tick over, got it running, but not to print.”

J: Have you any idea what business it was that owned the press originally?

C: “It could have been for printing Walkabout for all I know because originally it was acquired by the big magazines for their first colour printing, maybe pre-war…I’m not sure exactly where it all started, but it was four-colour technology. it was photogravure with etching with embossing, and it really prints the blacks. I did discover that it next went to South Australia to a business printing the foil that goes round champagne corks…a specialist application for it. It was so well made that it is probably still running today.”

J: So when was that?

C: “That was 1982.”

J: Light Vision had finished then.

C: “Yes.”

Colin mentions that Jean-Marc with other commercial photographers had a studio and darkroom in Armadale. Tired of driving Australia Post vehicles, he decided to work there, but the lack of a solid client base meant it wasn’t very productive. In 1982, Neil Wallace from Melbourne Etching Supplies, for whom Colin had worked as a student in the 70s, offered him a job in sales and marketing of their aluminium framing system, the mouldings for which Neil, a metallurgist, had designed. For four years, Colin successfully marketed their cutting service and mouldings.

He considered buying into the picture framing business, but in 1986, Colin’s father, for whom he had previously worked as a student doing deliveries for Bosisto’s, asked him to handle sales and marketing for their Moorabbin business. Colin returned to a management role, dealing with the new Therapeutic Goods Administration which in 1989 required them to have licensed facilities by 1992. Despite the 1989-1990 recession, their business thrived, allowing them to purchase a large factory site in Oakleigh South and the business expanded, eventually acquiring another large warehouse on the site.

Though it was rewarding to be part of the growing business Colin decided to leave in 2004 to pursue other interests. However, during the GFC, he returned as a consultant to help with stability issues related to senior staff. He continued consulting until his retirement in 2017.

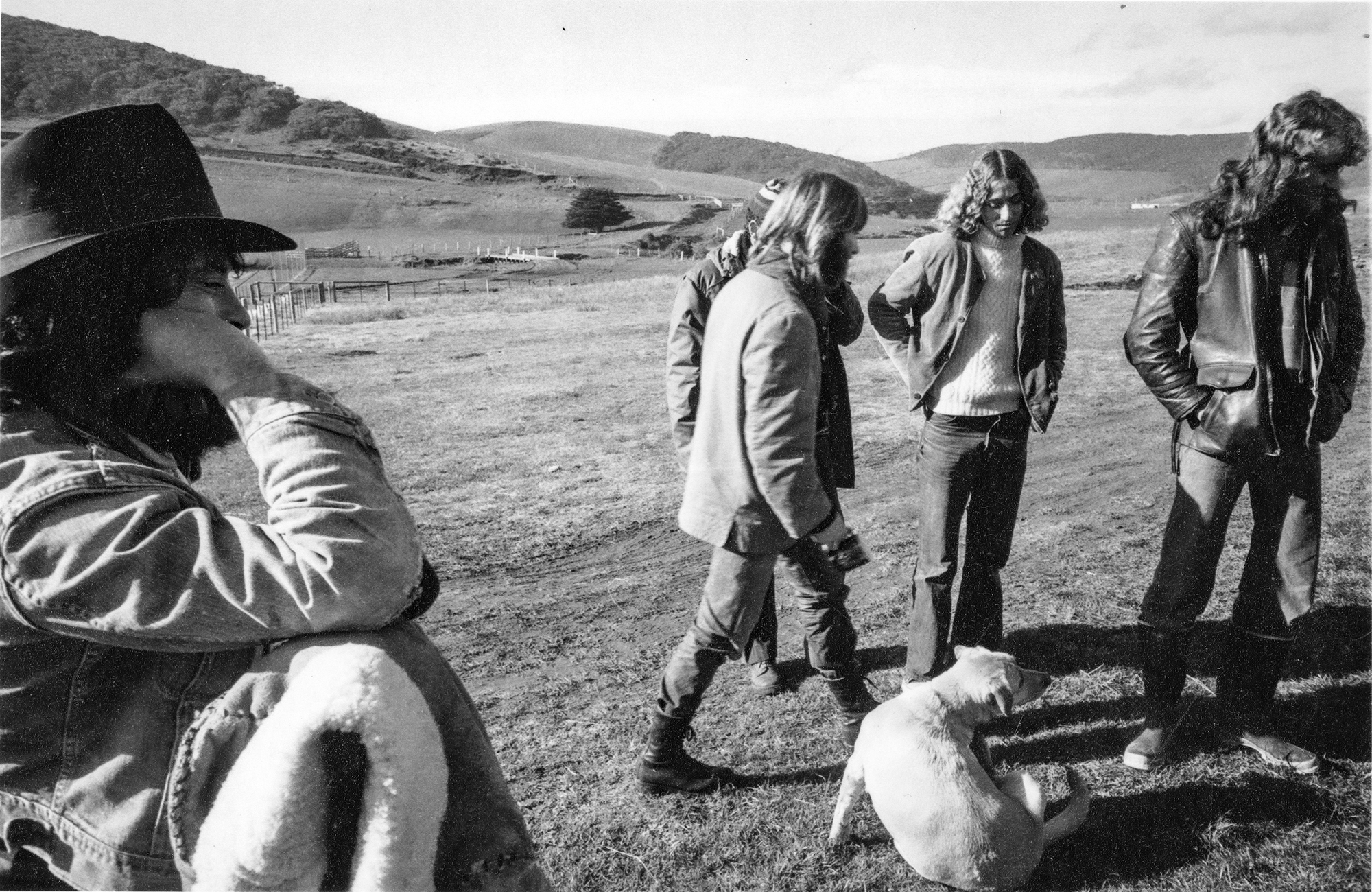

C: “When Dad bought Bosisto’s, in February ’75 I went up with him to the Inglewood [eucalyptus] farm, which is now grown to almost 10,000 acres, and documented it—I think I’ve shown you the book—so they’ve got all those photographs. They modernised the old building, and built a whole new manufacturing facility next door. My work’s in the offices up on the wall.”

J:…and the company promotes that historical fact that it’s an old company, long established…

C: “Yes the brand goes back to the 1850s and this year is the 50th anniversary of the Abbott family owning the business, so I’ll undertake a photographic project to celebrate and publicise that.”

J: Well this Museum of Australian Photography book of our exhibition is one huge project that you’re assisting with; there may be an Abbott name on the catalogue.

In an interview with Merle Hathaway, Colin reiterated that his experience at Prahran did not significantly change his work as he had already absorbed the influence of John Wong in Sydney, one of the 49 photographers featured in Graham Howe’s 1974 book on Australian photographers which includes 14 Prahran photographers as well as work by John Cato and Paul Cox.

Colin credits his creative thinking skills to his time at Prahran, but he believes that came more from interaction with his fellow students than from the lecturers. The diverse age range of his peers, from 19 to 35, developed a distinctive quality to their collective work.

Colin did not pursue a career solely in photography, but applied his creative skills in his family business, in advertising, promotion and public relations; which in effect, he asserts, was social media before the advent of computers. His education at Prahran instilled in him the principle that a photographer is only as good as their last job, motivating him to continually seek new and different projects.

Despite his primary career in the family business, Colin has maintained his passion for photography, producing several books, including Waiting Under Southern Skies, a collection of his work that has been well received amongst documentary photographers. Aside from his contributions to this significant Prahran Legacy project, Colin is documenting the Eel Festival at Lake Bolac, photographing the eucalyptus distillery for the family business, and continues recording Anzac Days. Despite the digital age, Colin prefers to keep things ‘old school’, inviting people to view his work in galleries rather than online, most recently his 2024 exhibition at MAGNET galleries. Colin’s dedication to photography has enabled him to blend creative skills with his business acumen for success in his career.