In photography, there’s certainly luck involved, but ‘unlucky’ just means ‘unprepared.’ When you spread the good fortune, luck multiplies, and that is the story of Andrew Chapman.

In photography, there’s certainly luck involved, but ‘unlucky’ just means ‘unprepared.’ When you spread the good fortune, luck multiplies, and that is the story of Andrew Chapman.

Born in 1954, in Melbourne, Australia, to Elizabeth, a writer, and John Chapman, export manager of the Australian Wheat Board, Andrew trained for his diploma in photography at Prahran College of Advanced Education from 1974 to 1976, under Athol Shmith, John Cato, and Paul Cox, and qualifying in 1980. He recalls that ;

“My older brother Chris and my father, John, had held an interest in photography when I was younger and they even built a darkroom in the larder. But being much younger I paid scant attention. My earlier years at Prahran were a liberating time for a young man whose only mediocre talent was that he could take an average photograph.”

The chronically underfunded photography department in the Visual Art building left a lasting impact on Chapman, who fondly recalls Cato’s apposite aphorism; “evolution thrives in adversity.”

Always at Prahran, Chapman, whether on assignments, to excursions, or in class, had the neck strap of a vintage Leica camera wrapped around his wrist, ready to stalk his quarry.

I and many of his fellow students were in awe of his dedication, and he encouraged imitation. He remembers;

“Colin Abbott was a fellow traveller in this regard, having lived in Sydney with a group of documentary photographers. He carried a Leica and was keen on unobtrusive street photography.

“My brother Chris had bought a 1936 Leica 3A with a couple of lenses for $40, advertised in the Trading Post newspaper and I surreptitiously took possession of the kit as he was travelling overseas at the time!

“My brother Chris had bought a 1936 Leica 3A with a couple of lenses for $40, advertised in the Trading Post newspaper and I surreptitiously took possession of the kit as he was travelling overseas at the time!

“It was not technique that I really learnt at Prahran (though that was there for the asking), rather it was about being introduced to the photographers that existed out in the wider world and the styles that they exercised.

“I was awed by the work of documentary photographers, the usual crew….., from The Farm Security Administration photographers, on to Henri Cartier Bresson, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Don McCullin and of course W Eugene Smith. I sought truth in photography and was hell bent on getting it, even if I did not have a clue how to go about it!”

Chapman was quick, in the midst of his second year of his study at Prahran, to record the fast-moving political scene on 11 November 1975, when after a series of dramatic events including a 1974 double dissolution and a budgetary supply crisis, the Gough Whitlam-led federal Labor government became the first (and only) government in Australian history to be dismissed by the Governor-General.

Like all the students, Chapman found the course always in flux, renewing itself as it adapted to the rapidly changing 1970s photographic culture;

“Athol Shmith, John Cato, Paul Cox in particular were photographers who had ‘The Fire’. They burned for their craft, and that rubbed off on their students who in turn had their respect. I well remember the day Cato came into the assessment room and put one of his first photo essays up on the walls of the room. This was ‘Tree, A Journey‘ and it’s fair to say that it blew most of us away. Cato’s work helped guide some of my image making away from documentary and onto landscapes.

“Athol Shmith at the time was working on his Anamorphic images and regaling us with funny stories from his working life. We once all went out for schnitzel at Transylvania Restaurant on Greville St. They were $3 each and accompanied by a gypsy violinist! Much alcohol was consumed and I remember driving Athol’s beloved Rover 2000 back to the campus with him sitting on my knee! We all continued drinking into the night at Jess Ward’s house in Hawthorn. Last person standing??? Athol of course.”

“Paul Cox and I did not get along so well. I had a healthy disregard for his urging us to study the book, Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintainence and I guess the stand-off continued until I left [he was failed in his fifth semester in 1976, then returned to complete his qualification in 1980]. Much much later in life I crossed paths with Paul whilst doing an interview for a documentary on John Cato. He was mortally ill from liver cancer at the time and desperate for a transplant.”

In 1978, by then dedicated to photojournalism, Chapman pursued every commission he could get, and was rewarded with publication in The Melbourne Times and Syme Community Newspapers, and freelanced for major publications including Time, BRW, and The Bulletin. His photographic subjects ranged from rural Australia and its diverse inhabitants and harshly beautiful Australian bush landscape, and to photographic encapsulation of lively Federal politics, producing this classic which outdoes any cartoonist’s characterisation of the Howard years…caricaturing his cartoon Menzies eyebrows and notorious Donald Duck lips as they heartily intone “rejoice.”

“Much of my working life I have always carried that documentary spirit with me. From my long term project photographing shearers and woolsheds, my political work and onto my later power station work, I have always kept that essence of truth in photography with me, mostly by waiting for events to unfold before me.

“A classic example of that is my image of John Howard, his wife Janette and grown family on election night at The Wentworth Hotel, Sydney 2004. When it became apparent that The Liberal Party had won, the family got up on stage to thank their supporters and concluded by singing the national anthem. The family all proudly singing in unison and that image just fell into my lap. I knew I had it the moment I took it. No need to look and check if it was good. To me it’s an image that supporters and detractors will both see value in. The Bulletin magazine used it across two pages.”

The magazine also highlighted, with a cover photograph by Chapman, the disenchantment with Howard that led to his surprise defeat at the 2007 election after 11 years of the Howard Liberal-National Coalition government.

The magazine also highlighted, with a cover photograph by Chapman, the disenchantment with Howard that led to his surprise defeat at the 2007 election after 11 years of the Howard Liberal-National Coalition government.

Earlier, in 1987, Andrew had been on the spot to record Bob Hawke’s triumphal third election to prime ministership.

TIME, also featured Andrew’s photo story on heroin dealing in Melbourne;

“Possibly one of the hardest assignments I had was for TIME magazine’s Australian edition, photographing the heroin epidemic across Melbourne’s inner suburbs in March 1999.

I had arranged to get in a car with two heroin dealers and to go and pick up a deal in Richmond. After doing so, we drove to the back of some 1960’s flats in Collingwood where the dealers, Matt and Mark, proceeded to cut the larger amount into street deals.

They then proceeded to inject themselves into their necks with eight times the normal street dose.

Sometimes you have to stress and work hard to gain an image, but in this case it just walked right up to me.”

Andrew continues to be dedicated to the idea of truth in photography;

“I want to leave a visual record that people can rely on. I don’t add things in before I photograph and I don’t take things out with Photoshop. To make a shot visually appealing, I just have to be sure to get it right in the first place”.

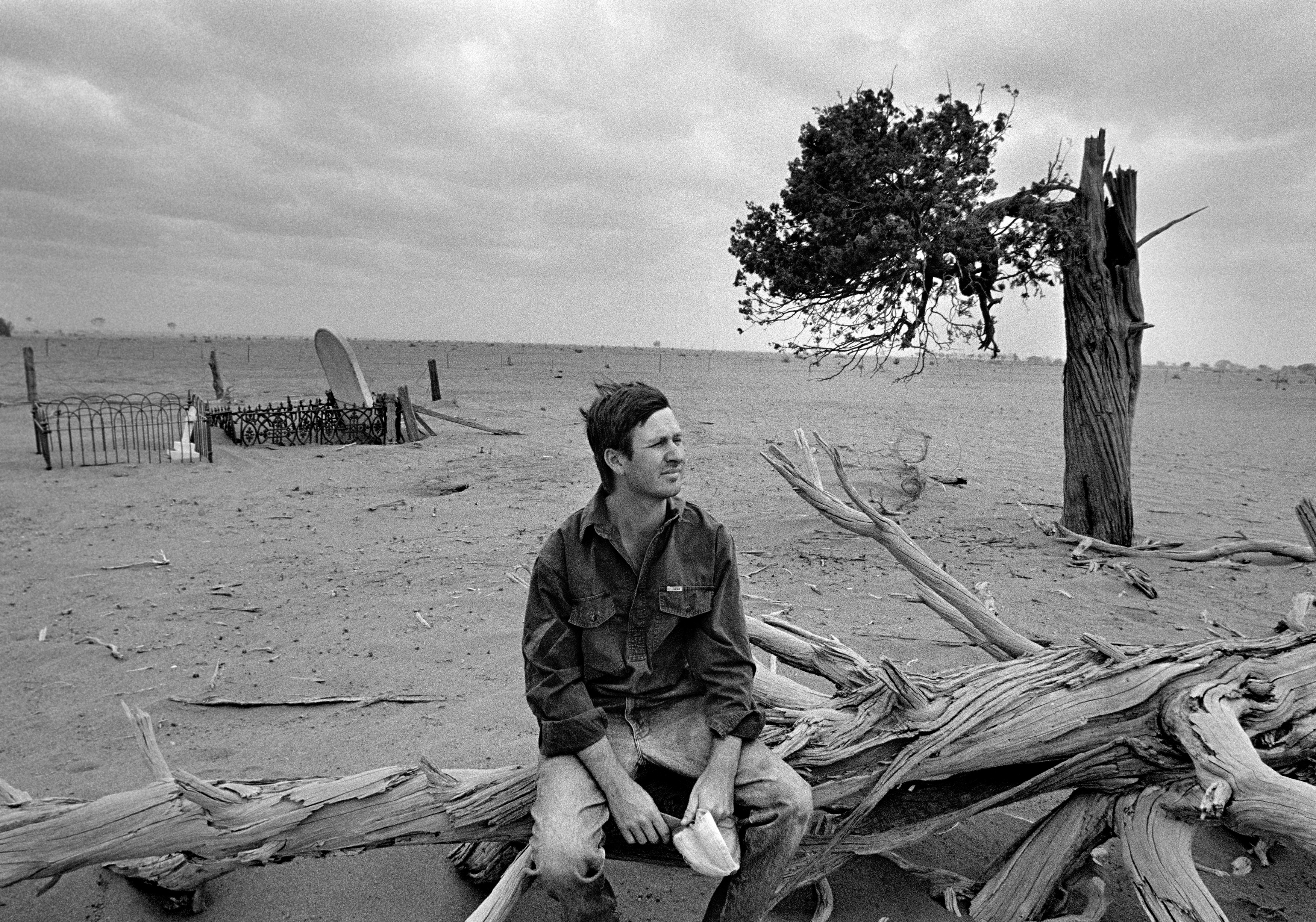

From 2006 onward, Chapman authored nine books and showcased his work in exhibitions across Australia, France, and the USA. His extensive travels across the continent were inspired by the work of Jeff Carter, and he encouraged fellow photographers to explore Australia’s “inner circle,” away from the urban centers and coastal areas.

In 2011 Chapman underwent a liver transplant, then faced a crisis when blindness was threatened by a viral infection. This experience prompted him to hold the 2012 exhibition which he titled, with typical Ocker understatement , Nearly A Retrospective. It presented an extraordinary four decades of his work. His reflections on the medical episode were captured in the documentary “Yellow,” which won the Lift-Off Global Network Best Short Documentary in 2019.

Andrew recounts experiences with liver transplants—Paul Cox’s and his own;

“Next time I met Paul Cox was when we were both visiting Cato in hospital towards the end of his life. Paul came up to me, gave me a big hug and told me he had received a donor organ transplant and how happy he was.

“It’s strange how life unfolds; the next time I saw Paul Cox, I was in intensive Care at The Austin Hospital following having had an unexpected liver transplant myself. I was close to death at the time and very weak, but he told me not to worry…that soon I would be up and about like him. It’s funny how life’s wheels turn!”

In 1998, Chapman co-founded the MAP Group (Many Australian Photographers), dedicated to revitalizing documentary photography traditions. He served as the inaugural president and spearheaded projects like Beyond Reasonable Drought, which documented global warming-induced drought across Australia and toured the country for five years.

Chapman’s mentorship extended beyond the MAP Group, and his contributions to the arts were recognized in 2014 when he was awarded the Order of Australia Medal (OAM). His solo exhibitions, including Giving Life and Wool & Politics have toured nationally, showcasing the development of his diverse body of work and his impact on our medium.

“It’s now been around 55 years since I first picked up a camera and fell in love with photography. Rarely does a day go by without me taking or thinking about images. I’ve been a lucky person in that regard and Prahran played an important part in the process.”

2 thoughts on “July 30: Luck”