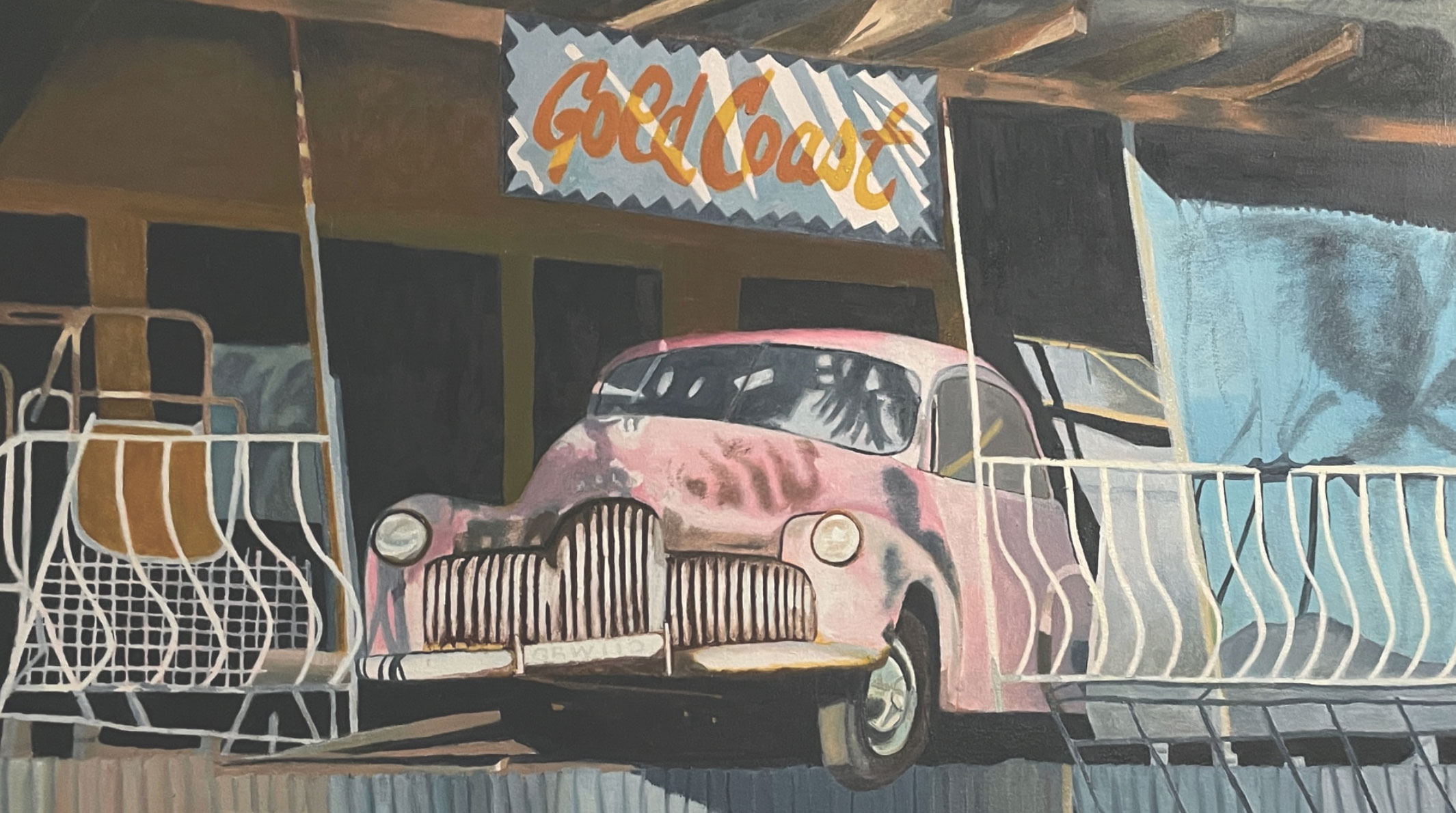

A social-realist eye sees in built surroundings social, historical and physical processes that can be pictured on film or on canvas to represent how we dwell in our environment, shaping it and being shaped by it.

Prahran College alumnus Martin Munz works in both those media and mentored others. Born in 1946, he is the son of Hirsch Munz who while serving in the Australian Navy married Estera Rosenblatt, a physiotherapist, in Melbourne in 1943 and returned to live in St Kilda. Martin remembers that:

“Neither of my parents were photographers, but I liked photographs as a child and enjoyed going through the family photos that were kept in a drawer in the living-room. Old photographs I enjoyed best, with their sense of being from another time and place, and I liked contemplating how they relate to the present; where and when were they from; and what were their stories. Many of them obviously did not come from 1950s Australia.

“I had a box Brownie camera when I was a young teenager with which I took family pictures, of Mum, Dad, me, and the dog.

“Then I got a Pentax 35mm camera at the end of my high-school years. Film was processed at the chemist, later at a local photographer’s shop in Elsternwick. As I got older, I took photos of my teenage and university friends.

“My schooling was academic. Although I did art and liked experimenting with coloured paints, an art teacher discouraged this and made me paint a portrait of a friend which wasn’t a success—the teacher and my class mates said it was awful. I didn’t like it either.

Martin was aware of the arts as his father was (amongst other things) an English and Yiddish language writer and public speaker. His parents, whose friends included writers and artists, had a small library with art-books, including Rex Batterbee’s, Modern Australian Aboriginal Art (1951). Yosl Bergner, the noted Australian social-realist painter had been a family friend before migrating to Israel in the late 1940s:

“So, I knew that there was another world, and there had been another time, other than the round eternal of suburban 60s Melbourne. However, I was not encouraged to pursue those things but was expected to become a lawyer, which I understood as being a way to make the world a better place and make Australia more egalitarian. Towards the end of my Melbourne University law degree in the late 1960s, I became a member of the university’s Labor Club. While setting up a rudimentary B&W darkroom in the basement of a university college, I discovered some old photos of nineteenth-century college luminaries that were subsequently restored and which were prominently displayed. I printed B&W photos of friends in that darkroom as a distraction from my legal studies.”

“I was ambivalent about the law, its social functions, the complex absurdity of much of its processes and its social biases. With friends I participated in the Fitzroy free-store where we gave stuff away. I was active in establishing free legal services around inner Melbourne in the early 70s: the Fitzroy, and then the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service, and then the Free Legal Service in St Kilda where I moved from Fitzroy. I became a lawyer, but most of my friends were not; my then partner Carol Hardwick was an architectural historian researching the influence of Art Deco on Victorian architecture, and art historian friends were researching Australian art and the Labour movement.

“Radical Russian and German photo media was being rediscovered at about that time, and I was aware of Australian and European art of the inter world-war and earlier eras. I was impressed with its wit, verve, and radical intensity, and Australia’s radical political cultures of the 1930s and 1940s which friends were researching. Some of those artists and writers had been friends of my parents.

“Though I cannot recall how I heard about Prahran College, Prahran Tech as it was then known was a byword in Australian art. A friend, also a disaffected law student, later cartoonist, Peter Nicholson, was attending Pam Hallandall’s drawing classes. I was doing some part-time law teaching in the Business Studies school at Prahran while working as a barrister, so I became aware of the Photography department. I may have also attended some short black-and-white courses the department ran in the mid-70s as I recall working in the darkrooms after-hours before I became a full-time student there in 1978.

Maurice Hambur, who was a then recent Prahran Photography graduate appointed by John Cato into the Extension Program became Martin’s photography tutor with a view to my getting an entrance folio together:

“I cannot remember what the images were, but they were black-and-white 10x8s mounted in bottom-weighted black cardboard mounts, probably conventional and rather funereal. I cannot remember what John Cato and Derrick Lee, the lecturers who I think assessed them for the 1978 year’s intake, said about them.”

Martin lived on the Esplanade in St. Kilda while he was a student at Prahran College from 1978-1980, near the corner of Fitzroy St., still teaching law part-time in the Prahran Business Studies school. Later, he was also doing some art-reproduction photography for Georges Mora’s Tolarno Gallery. Earlier in the 70s, Martin and Carol had moved into an apartment next door to the Tolarno restaurant in Fitzroy St., and he’d become friendly with Georges and his sons William and Tiriel, and Philippe when he visited from London. They were regular visitors to the gallery Georges established in one of the back rooms adjacent to his Tolarno restaurant.

“I recall few details of the classes at Prahran but I do remember John Cato saying one day that if anyone wanted to be remembered as a photographer, just walk down any main street, and take consecutive photographs of the buildings on either side of the street. These were prophetic remarks considering my current paintings which, although they are not serial images, are realist and are images of mundane landscapes and regional subjects.

“I was impressed with Norbert Loeffler’s art history classes. He seemed so dedicated to his work, as confirmed when we know he was doing most of them as a volunteer! Murray White was extremely patient with our demands. Brian Gracey was a font of technical wisdom and very patient too. I think it is due to their support that I reached the apogee of my technical competence, hand-processing six sheets of 5×4 inch E6 transparency film from a Grafmatic film-holder. Paul Cox seemed to have me type-cast (not wholly without reason) as a left-wing intellectual type and therefore dubious. I seem to recall a character in one of his films, called Martin, who is arrogant and doctrinaire. However, Paul did recommend me for a job after I graduated.

“The guest lecturers I best remember are Julie Millowick, Chris Long, a young art-historian from Tasmania who seemed particularly switched on, and John Gollings.

“Athol Shmith, then in his last year of teaching in 1978, I admired for his terrific fashion work and general sophistication. John Cato, for his formal black & white studies, and Paul for his contribution to photography and Australian film. I remember Paul working up a panel of coloured polaroids one day in class. I’m not sure if he was demonstrating or just happened to be working on them, but it was marvelous to see what he conjured up by rubbing the image with a blunt stylus, and I think heating the polaroids too.”

The electives he took, the class assignments, and the assessments, have faded from Munz’s memory, though a landmark was his participation in the 1978 Prahran student exhibition at the Kodak Galleries of pictures they had taken at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Instruction was balanced, he feels, between the practical and technical against the theoretical and historical by courtesy of Norbert’s classes.

Of his contemporaries at Prahran, Martin says that though he has not kept in touch with them:

“I was aware of Bill Henson‘s and Polly Borland’s reputations and some of their works. I found reading here about some of my direct contemporaries, and of Julie Millowick’s and Nanette Carter’s careers, quite moving. It was good to see that they have really done big things in photography, video and academia. I was really interested to read Jim McFarlane’s story and of his subsequent career, and Andrew Chapman’s, although I was aware of his work as one of his photographs, ‘John Maher on his fathers property at Minyip Victoria’, is of one of my brothers-in-law. Chris Köller‘s achievement in becoming head of Photography at the Victorian College of the Arts, and his many photo and video projects, are impressive too.”

Vaneigem, Raoul (1970). Treatise on Living for the Use of the Young Generation. United States: Situationist International. Illustration: Gordon Parks (1948) Red Jackson, Harlem, New York (detail)

Vaneigem, Raoul (1970). Treatise on Living for the Use of the Young Generation. United States: Situationist International. Illustration: Gordon Parks (1948) Red Jackson, Harlem, New York (detail)

“Before and while at Prahran I was reading the 1930s critic Walter Benjamin, and was very taken with the lay-out and graphics in 1970s pamphlets from the Situationist International such as Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, and Raoul Vaneigem’s Treatise on Living for the Use of the Young Generation.

Twenty years after the events in Paris, Sydney’s Performance Space chose as the topic of its first Media Night, Mai 68 – The Idea of Change, with Munz giving the final paper in which, as Christopher Allen in The Sydney Morning Herald of 16 May 1988 reported, he reminded listeners “that it was the situationists who first spoke of the ‘society of spectacle’ and that the idea originally had a critical force. Today it is more often associated with a complacent nihilism.”

“I was interested in the art of Yosl Bergner, Nutter Buzacott, Noel Counihan; in Constructivism and early C20th Russian art by Sonia Delaunay, Vladimir Tatlin, Aleksander Rodshenko and El Lissitzky; German photomontage and the New Objectivity of John Heartfield; George Grosz August Sander and Giselle Freund; and American Precisionists Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth.

“I was aware of the tradition of Australian political art such as trade union banners, and I was involved in labour-aligned art work with the Unemployed Workers Union and the Art Workers Union. I volunteered at 3CR, the Melbourne community radio station. Mick and Terry Counihan were friends too, the sons of Noel Counihan who with Yosl Bergner was a significant Australian Social Realist in the 1930s and 40s.”

“Photography has been important in my life, in an indirect way. Although I practised it and video in the years immediately after I left Prahran, gaining some prizes and residencies, my career panned out to be in arts administration. I now produce oil-paintings based on my photographs, although I don’t regard myself as a photorealist painter.

“St. Kilda was a very familiar place to me. I’d lived there as a young child and I was happy to return to live there from the mid-1970s until the early 80s, first in Fitzroy St, and then on the Esplanade where Carol and I lived until 1982. I initially had a darkroom in a hall cupboard at Mardi Place, then in one of the brick sheds at the back of the flats. Then we moved to Darwin when I became an artist-in-residence at the art-school there.”

While living at Marli Place and studying at Prahran Martin was interested in realism and documentation. He photographed the neighbourhood, experimenting with various photographic processes and camera formats.

Martin’s Marlboro Man is included in Reimund Zunde’s 1982. Photography : An Approach for Secondary Schools published by the Education Dept. of Victoria, Curriculum Services Unit, Special Services Division in association with the Secondary Art/Craft Standing Committee. Beside the photograph is a statement that accords with his artistic intent in making photographs and later, paintings:

“This photograph is a photograph of a photograph. Photography is a vast industrial undertaking by a few corporations, catering to a vast market that reaches into every household.

Everyday professional photographers use all the skill and imagination at their command to produce images that indicate, celebrate and promote, and that at the same time demean, trivialise and control.

The Marlboro Man is one of photography’s most persistent images, signifying tough, masculine, no-nonsense, individual choice in the never-ending pursuit of freedom, quality, integrity, discernment, all to sell a mass-produced, uniform and noxious product.

Photography as art has an uneasy relationship to photography as industry. That relationship is what this photograph is about.

It would be better if more photography as art concentrated on the relations of production of photographs, thereby diminishing the hold that photography has on us.”

Some of those photographs are collected in the Port Phillip Collection and are drawn from different projects from that time. Then he worked in video, initially in collaboration with Juan Davila, the Australian-Chilean painter.

“I remember the Photographers Gallery in Punt Road, Joyce Evan’s Gallery in Richmond and Brummels in South Yarra all showing photography in the 60s & 70s but cannot recall any of the exhibitions—I was more interested in photographic realism and political photography and video. I don’t think I developed a particular photographic style, rather I was content focused, although my individual work didn’t approach the critical originality I admired in other artists.

“I suppose the photographic related achievements I’m most proud of are the St.Kilda photos in the Port Phillip collection especially the series of cibachromes made in and around water with a Nikonos; and the videos I made with Juan Davila, in particular the Ned Kelly, as it was I who proposed that subject to Juan. In that tape we ‘deconstructed’ the Australian bush-ranger’s image via homo-erotic imagery, appropriation of parts of Mick Jagger’s 1970 film of the same name, and its soundtrack, The Wild Colonial Boy.”

From 1978, Martin’s final year, until around 1985, he had solo shows, including two at Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne. He also participated in group shows as a photographer in St. Kilda Festivals (1980 & 1981) and Prahran community shows (1978) as well as Art Workers Union exhibitions (1980 & 1981). Martin produced videos in collaboration with Juan Davila that were shown at Tolarno (1983 & 1984) and at the Experimental Art Foundation (1984) in Adelaide, at Melbourne’s Australian Centre for Contemporary

Art (1985), and internationally. He also collaborated with Adelaide sculptor Steve Wigg, producing videos in installations shown at various venues, including Anzart-in-Hobart (1982 & 1985), precursors to the current Asia-Pacific Triennials.

Retrospectively surveying his experience of Prahran College, Martin concludes that…

“…over the 1960s and 70s, Prahran College produced photographers who helped established photography as an independent artform in Australia, consolidating the work of Athol Shmith, John Cato and Paul Cox. Photographic formalism with its entailments in commercialism and the gallery system may have superseded earlier politically radical photo media practices that were important in the history of photography elsewhere. Artists like Tracey Moffat and the late Destiny Deacon, amongst others, continued to use photography for radical artistic and social ends, which is not to detract from the achievement of Athol, John and Paul and my contemporaries.

In 1982 after securing an artist-in-residency at the then Darwin Community College (DCC), Martin became a member of staff teaching Photography and Film Studies there. Carol Hardwick, his partner, taught Art History at the same school:

“I was not conscious of a Prahran slant to my photographic teaching which was probably influenced by my interest in Social Realism. There was a minor controversy when some students complained about my Film Studies course including classics of the German and Russian avant-gardes then freely available from the National Film Library in Canberra.”

Margaret Simons, interviewing Martin for The Age in June 1983 noted how he photographed and filmed First Nations peoples around Darwin and their ceremonies in cooperation with Aboriginal groups:

“One of the things that is good about the Northern Territory and Darwin Is that it is one of the last places where Aboriginal societies are still to some extent viable. Darwin is the gateway to the Northern Territory, and so photographers are there all the time. They go along and poke cameras at Aborigines, and then the images are used in totally inappropriate ways, as far as the people themselves are concerned. They are quite glad to have a tame photographer along to do what they want and cooperate with them. Then the Images are used in the ways they want them to be used. They are in control at every step.”

The couple remained in Darwin until 1985 and their two daughters were born there. Carol was also researching the work of B. G. Burnett, the Commonwealth’s principal architect for the Northern Territory. Martin joined Carol in a community campaign to preserve some of Burnett’s houses that were threatened with demolition at that time, but were preserved. He designed many well-known innovative, modernist, climate-appropriate heritage buildings in Darwin and Alice Springs in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. Burnett’s classic tropical houses fared better in the Darwin’s cyclone Tracey of 1974 than many more recent structures. His houses were the inspiration for the contemporary Darwin architects Troppo, highly regarded for their light-steel framed houses of timber, cement and corrugated iron sheeting, glass-louvers, and flywire.

“I continued my practice as an individual artist, producing video art and photographs, I collaborated with art and craft advisers in Aboriginal communities in the Centre and Top End photographing for catalogues, providing access to the facilities at the DCC and facilitated connections between them and my students leading to longer collaborations.

“I produced Gurindji Freedom Day the video-tape that documents the 1984 re-enactment of the strike and walk off from the Wave Hill cattle station by the Gurindji community on 23 August 1966. 100 Gurindji stockmen and their families walked off Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory in that strike that ushered in the contemporary phase of the land rights movement.”

After the family left Darwin in 1985, Martin became Director of the Tin Sheds (University of Sydney Art Workshop), the artform studio-based joint facility of the Architecture and Fine Arts departments, where he also taught a Photography course:

“The Sheds had a storied past as an alternative community art facility, draft-resister haven during the Vietnam War and was also a venue for early Mental as Anything gigs. The Sheds, along with The Yellow House and Inhibodress, was one of the foci of the Sydney artist-run contemporary experimental art and music scene of the 70s, the Sheds being at the more political end of a broad spectrum of artistic activity.

“When I arrived, the Sheds had been integrated into the formal teaching curricula of the university departments concerned and many figures associated with its earlier halcyon days had left, however a women’s poster-making collective (Lucifoil) still operated from it. I sought to re-invigorate the Sheds and re-established the small one-meter square Avago gallery in the front corrugated iron fence on a major road that bisected the university, as well as a larger gallery elsewhere on the premises that operated from (1985-89).

For its inaugural show, Avago Gallery played a peripheral role in the scandal of the Weeping Woman theft from the National Gallery of Victoria in 1985 when it exhibited Juan Davila’s copy of the stolen painting some few days after the theft.

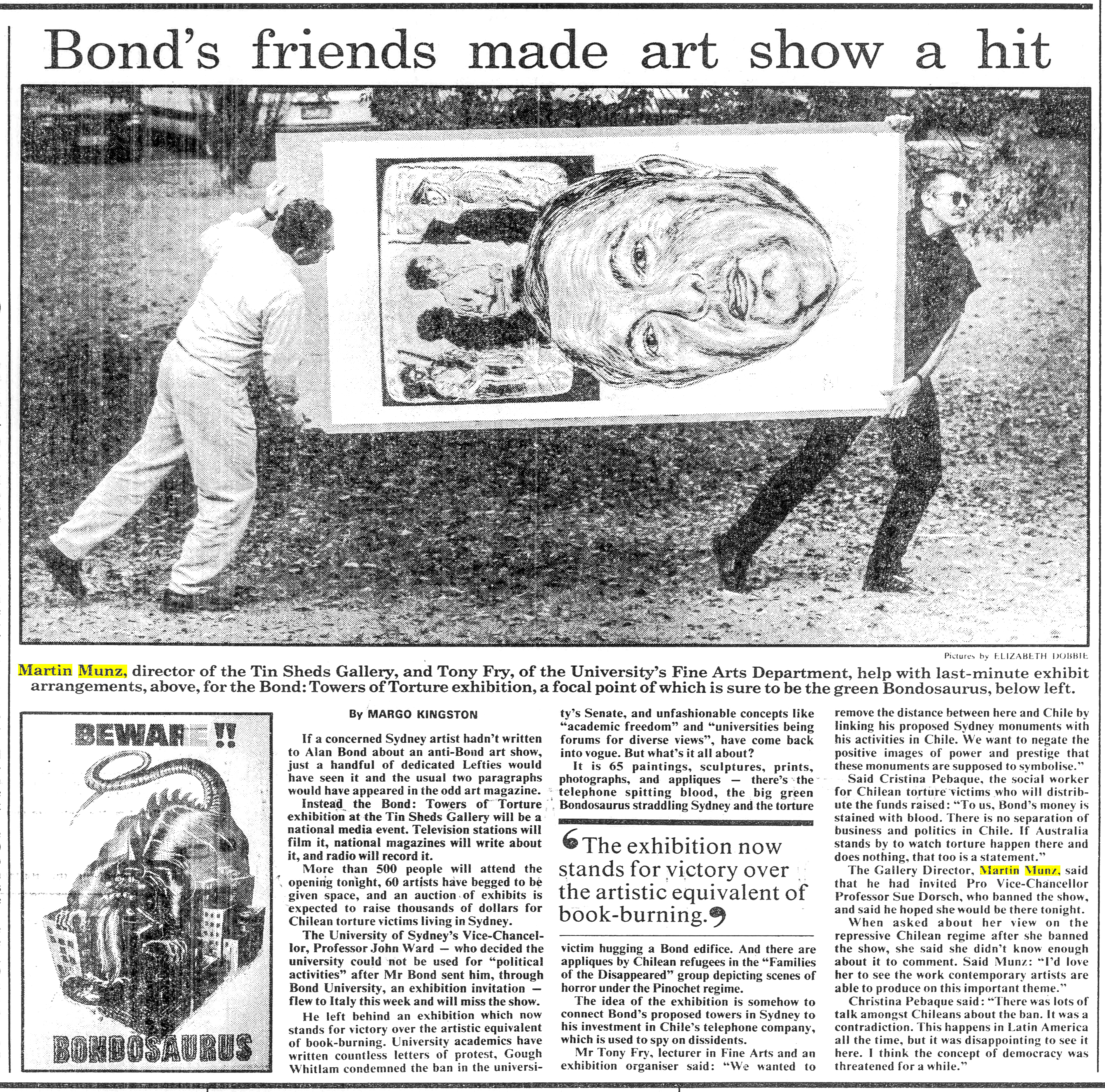

“However, that scandal was eclipsed when the university instructed me in September 1988 to stop an exhibition Towers of Torture in support of Chilean political prisoners themed around architectural design and repression; appropriate subjects for the Sheds given our institutional setting and history of political engagement. That show was prompted when Alan Bond, then owner of the Chilean telephone system which was compromised by its association with Chilean dictator Pinochet’s security police, proposed a multi-storied building in the Sydney CBD (now ironically named the Chifley Centre). I could not follow the instruction to effectively ban the show, and then it became apparent that Bond Corporation via Bond University had influenced executive officers at the university to axe it.

The ensuing scandal was front-page news in Sydney and, despite the reversal of the ban twelve days later, exposed the underside of university politics:

“Divisive issues in contemporary art were also revealed when Juan Davila opposed the project on the grounds that art should critique only art and not wider political issues, which he argued reduces art to mere illustration. Whatever the merits of that argument, and whether his oeuvre actually observes that distinction, it is at variance with some significant twentieth- and twenty-first-century art—like Guernica—and what the Sheds were about.”

In 1990 Martin became Director of the Experimental Art Foundation (EAF) in Adelaide, a 60s/70s artist-run initiative that had survived and was by then part of the metropolitan contemporary art-space network funded by the Australia Council, and state governments.

“My time at the EAF was not marked by controversy, save that I declined to meet the Queen who opened the purpose-built Lions Arts Centre where the EAF had new premises. I left in 1991 as Carol was unable to find work in Adelaide, and although our marriage was to dissolve amicably, I returned to Sydney to help her support our children.

“In 1992 I commenced work at the Australia Council’s Visual Arts Craft Board (VACB) in Sydney. I felt it was inappropriate to continue practising as an individual while having a role in managing artists’ grant assessment procedures, not that I had any decision-making role in those programs, but it was potentially a perceived conflict-of-interest.”

Although Martin’s public practice as an artist ceased until he retired from the Australia Council in 2006, he took frequent courses in painting and drawing and made artworks at home. While there, he worked in various roles in the VACB, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board, and Corporate Affairs, including four years working remotely for the Council from Hong Kong where he had moved with his partner who had a teaching position there. While there, a Chinese ink-painter, Alan Chung, taught him Lingnan ink painting, a ‘modern’ form of ink-painting that developed in early twentieth-century Canton and is a contemporary style of painting in Hong Kong.

In 2007, Martin moved to the Northern Rivers region of NSW and resumed exhibiting in 2008 with a text painting made some years earlier, White Lies/‘Unlike Many Other Places Australia Has No History of Violence She Said’. He also exhibited drawings in 2010 and commenced a painting course at the Northern Rivers TAFE in Murwillumbah. Martin lived in New York City for eight months in 2011 and attended painting classes at the Art Students League on West 57th Street. Since then, he has been exhibiting paintings every year or so after completing his TAFE painting course in 2013.

During his exhibition Art Imitates Life, at Mist gallery in January 2024, Martin described to the Byron Shire Echo his motivation in representing the quotidian, built surroundings of Murwillumbah: “I ask how can the social processes that are at play in it be pictured. I intend my paintings to evoke dwelling, a quality of being there resulting from the folding together of human history, land, and sky.

“I want my paintings to work through pictures of the regional built environment to evoke issues beyond locality. By including street signage, light poles, and motor vehicles in my paintings I hope viewers might reflect on the historical and physical processes that shape our environment, and where they are going.”

Of the impact of digitisation on his art practice, Martin remarks that most significantly it has:

“…freed me from the weight and complexity of a 35mm camera and lenses. An iPhone enables me to take the photographs I use as the basis of my paintings, results that previously would have required darkroom processing and printing that can now be achieved, for my purposes, with the editing functions on a phone and simple printer!”

Martin remains engaged and astute. In 2021, The Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal published Martin Munz’s article which critiques former intelligence officer Dr John Fahey’s chapter 17 in his book, Traitors and Spies on Australian intelligence history, particularly its allegations against Martin’s father.

His article examines the treatment of Australian Yiddish and English literary and social activism in the mid-twentieth century and addresses Fahey’s false claims that Munz’s father Hirsch, a co-founder of the Australian Jewish Historical Society, was a Soviet Military Intelligence officer and led a spy-ring of Jewish businessmen in Melbourne from 1927 to 1955. Munz critiques the book’s historical methodology, factual accuracy, and its failure to recognise antisemitic biases in the Australian security files used by the author. The article also highlights the unwitting reappearance of antisemitic stereotypes in the book, reflecting a period when such biases were common in Australian security history.

Interviewed by Jen Kelly in the Herald Sun of 18 September 2020 Martin said his father’s business as a wool broker after 1947 continued his earlier research career with the CSIRO, and employment in the textile industry from 1928 to 1942, and that volunteering for service at the outbreak of World War II, he was knocked back due to short-sightedness, but was accepted when he volunteered again in 1941:

“There is no basis for linking my father’s business to a network of GRU commercial front companies. Based on the thin coincidence that my father arrived in Australia from Poland at about the same time as the ‘Polish illegal’, supposedly the deep agent of the Soviet military intelligence GRU, Fahey contends that my father was therefore the ‘deep agent’. However, in Fahey’s telling, that person was a Jewish refugee. My father was a sponsored migrant to Australia. He was not a refugee, but he was Jewish.. Dr Fahey has produced no evidence of his father being in contact with Solomon Kosky and Jack Skolnik.”

In the ‘Letters’ section of The Canberra Times of 17 Mar 2024 (p.12) Martin, an anti-Zionist since his 3CR days, writes under the heading ‘Gazan refugees are in limbo’:

“Families and individuals who escaped Israel’s assault on Gaza, and who were in transit to Australia, have been placed in limbo in marked contrast to Ukrainians escaping Russian aggression who were welcomed. Why are Palestinians escaping war treated differently? What justifies such bureaucratic cruelty? Previously, the government halted aid to UNRWA for Palestinian refugees on a trumped-up case presented by Israel that has not stood up. Now the government has cancelled previously issued visas on dubious grounds. The cancellation of Temporary Entry Visas for Palestinians escaping Gaza with family in Australia appears to be another example of administrative discrimination by the federal government against Palestinians. The circumstances of the visa-holders have not changed.

“Martin Munz, Murwillumbah, NSW”

Martin’s work is held in public and private collections in Australia and internationally, including the Australian National Gallery, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, Charles Darwin University, NT and the Port Phillip Collection, Victoria.