Here is a book that Australian photographers and photo-historians didn’t know they were waiting for, but will now find indispensable.

Here is a book that Australian photographers and photo-historians didn’t know they were waiting for, but will now find indispensable.

For several years Professor and Assoc. Dean at RMIT Daniel Palmer, and Martyn Jolly, Honorary Associate Professor at the Australian National University, together undertook research into the history of Australian exhibitions, from which they maintained an ever-growing online timeline with grants from the Australia Council and the Australian Research Council.

Of course, in the process they identified a number of likely “Australian firsts’, among them the reasonable assertion that this British colony’s first gallery was “Newland’s Daguerrean Gallery” opening in George Street, Sydney in February 1848, a date approaching ten years since France had donated the Daguerreotype process to the world. That this first ‘gallery director’ was a peripatetic Briton is beside the point of course.

Jolly, specialist in the history of the “magic lantern” and co-author with Elisa deCourcy of Empire, early photography and spectacle : the global career of showman daguerreotypist J.W. Newland, hides light under a bushel in not mentioning his discovery that the same James William Newland, was also the maestro of April 1848 lantern shows at the Royal Victoria Theatre, Hobart, of a “beautiful collection of dissolving views” by “powerful oxy-hydrogen light” — another Australian ‘first’? It’s an omission forgivable since Empire was published nearly simultaneously with Installation View. Newland during his short stay moved his portrait studio from Sydney to Hobart and displayed portraits of Pacific Islanders and views from his previous three years journeying through Central and South America, the Pacific and New Zealand, before before his departure to Calcutta where in Uttar Pradesh he was an incidental victim of the 1857 Indian Rebellion.

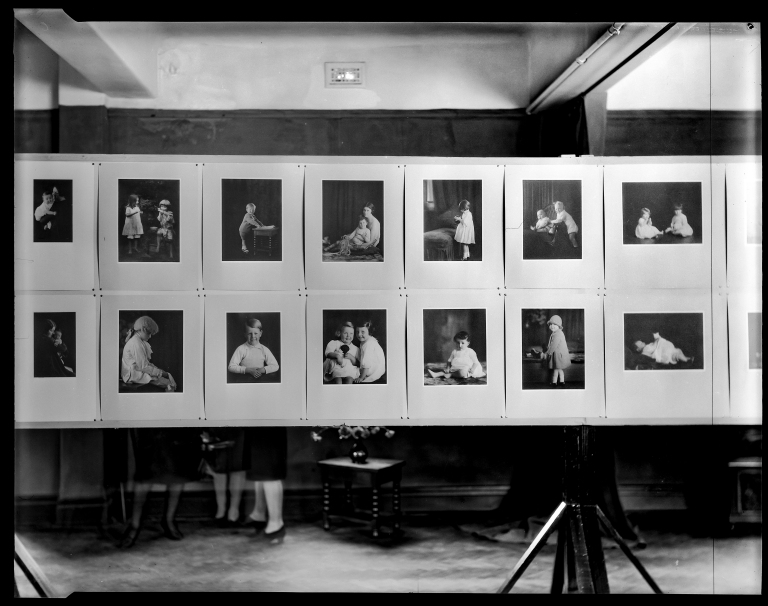

Amongst more emphatically Australian ‘firsts’ Installation View picks out, though he was New Zealand born, Harold Caxneaux‘s solo exhibition by an art photographer in a gallery setting (1909), recorded by him on this now broken, cracked and peeling glass plate, and Ruth Hollick‘s solo, the first by a female photographer (1928); the National Gallery of Victoria’s establishment of the first state gallery department of photography and the first to show photography (1967 and 1968 respectively); Sue Ford, the first woman to show photography at a state art gallery (1974); a first permanent photography centre, the now mothballed Australian Centre for Photography (1974); and firsts in relation to photography’s acceptance into exhibitions of art; at Perspecta (1981), and the Biennale of Sydney (1982), and the first photographer representing Australian art at the Venice Biennale (Bill Henson, 1995); the first large-scale exhibition of Indigenous photographers (NADOC, 1986); and so on, but beyond mere precedents, you will find the purview of this history nuanced and original.

Cazneaux’ and Hollick’s record shots of their shows demonstrate how ephemeral visual documentation of exhibitions can be, and the written record is just as fragmentary….appropriately the book’s foreword warns of “Photographic Amnesia.” Some of the shows were performance-based (Chapter 13, The Performed Photograph) and their record consequently fugitive, like colour prints from the eighties which are now visibly fading away.

Trace of South Australian media artist Stan Ostoja-Kotkowski‘s performance of Echoes, photographic and electronic projections onto a nude model has vanished for example. The authors’ persistence in accessing information despite such constraints is just part demonstration of the depth of Palmer’s and Jolly’s research that expanded the online chronology, and which despite the interruption of COVID, produced the book I have just purchased and eagerly read, which is richly illustrated from their delving into a scattered archive.

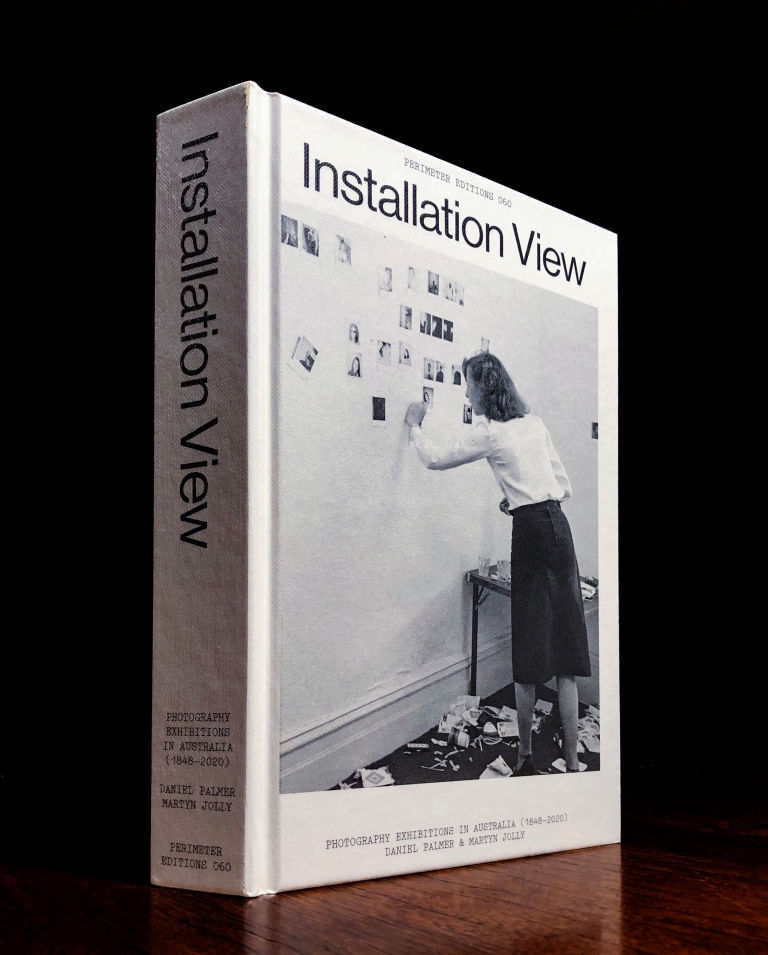

The joint authors identify it as a ‘source book,’ and more significantly they describe it using a once-common photographic term, a ‘parallax view,’ referring to the offset between views of the subject in the separate viewfinder compared to the lens of a camera. The metaphor applies given their different academic perspectives, and refers also to the way the finely-grained chronology is superimposed by their commentary as in a rangefinder eyepiece. In turn that has been calibrated by interviews and discussions with curators of photography, and lifelong engagements by both authors with photography. A comprehensive historiography, elucidated specifically in the chapter “Australian Photography History on Display,” is implicit throughout.

This is a history with a difference. In examining an escalating frequency of exhibitions we learn about the socialisation of the photograph — its assimilation by audiences and acceptance by commentators — but also the way an exhibition is the photograph’s (and photographer’s) “social face”.

In that regard, the timeliness and urgency of this volume is eloquently conveyed in the authors’ witty choice of cover image; a woman examining prints in a 1978 exhibition at one of the world’s earliest ‘artist-run’ commercial photography galleries, Brummels in Melbourne. The picture is of The Debris of Surprise organised by Rennie Ellis who convinced Polaroid to supply their cameras with ample film, and stimulation in the form of copious champagne, so that the invited participants could photograph each other, the results being pinned to the walls and left, along with the debris of overflowing ashtrays and empty glasses and bottles strewing the floor, for the duration of the show.

Illustrations are judiciously selected with many rarely or never seen before. But a false impression conveyed by photographic records of the earlier exhibitions discussed is that they had no, or very sparse audiences, apart from stuffed kangaroos. That noticeably changes as newspaper photographers started to visit shows in the 1960s and audiences themselves started bringing cameras (to photograph each other) in the 70s. The impact of “Feminist Photography Exhibitions 1971-89” (ch.20), brought experiments with formats and venues, exemplified in Micky Allan‘s My Trip, 1976 vis-à-vis Wes Stacey‘s serial snapshots at The Australian Centre for Photography The Road, 1975 in Chapter 17 “Photoconceptualism”. And the exhibitors recorded them, most vividly by Allan for her first major solo exhibition, Photography, Drawing, Poetry-A Live-In Show in 1978, amongst domestic furniture with the artist present to interact with audiences (installation shot, like the show, hand-coloured), and her Pavilion of Death, Dreams and Desire: The Family Roominstalled in Adelaide’s Rotunda in Elder Park, during the 1982 Festival of Arts, bringing her back to our attention in Chapter 37 “Photographs in Public Space.”

Installation View reveals that women (or indigenous, or non-European heritage) photographers were not invited into the first “International Touring Shows” (Chapter 35) from the Australian Centre for Photography (to which Chapter 14 is devoted) a prejudice the authors note in their quotation of Deborah Ely, a later director of ACP;

“It is a characteristic of the early years of the ACP that its governing culture was exceptionally male … “debate” between the founding fathers of ACP and feminists grew up over the years and persisted into the 1980s.”

Feminist critic Lucy Lippard is shown in one illustration at George Paton gallery visiting at the invitation of Kiffy Rubbo, (curator there 1971–1979) from the United States as part of celebrations for International Women’s Year. Though it’s not mentioned here amongst discussions of independent galleries like Marianne Baillieu‘s avant-garde Realities Gallery in Toorak which exhibited Mark Strizic, Bill Henson and Grant Mudford in the 1970s, Lesley Dumbrell accompanied Lippard to Pinacotheca which showed male conceptualists Roger Cutforth, Dale Hickey, Simon Klose, John Nixon and Robert Rooney using snapshot photography (Chapter 17). It is rumoured that when director Bruce Pollard invited Lippard to view the stock room, she explained she was interested only in seeing women artists and when he was unable to show her any, Lippard walked out.

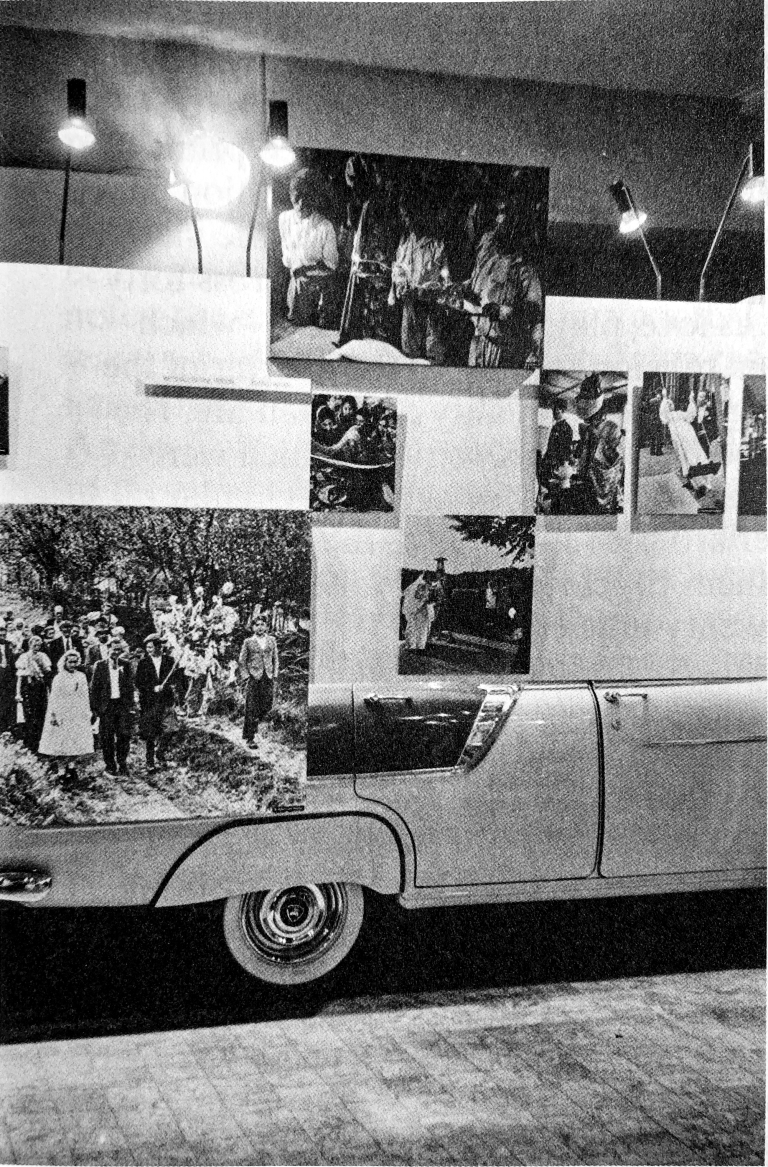

Wayne Miller (February 1959) The Family of Man installed at Preston Motors Showroom on Russell Street, Melbourne

Wayne Miller (February 1959) The Family of Man installed at Preston Motors Showroom on Russell Street, Melbourne

There is more to be learned from the authors’ analysis of installation photographs, for example Wayne Miller‘s documentation of The Family of Man display panels against the gleaming flank of a Holden station wagon in the Preston Motors showroom – the only venue large enough to display the MoMA blockbuster when it arrived in Australia in 1959 and which the authors note, in one of their many pertinent observations of coincidences and interconnections, was adjacent in Russell Street to the present day Katsalidis’s Hero apartments where Julie Rrap‘s Overstepping of 2001 a towering digital montage (not illustrated) of a woman’s feet morphed into stiletto heels, inaugurated a dedicated art billboard in an instance of “Photographs in Public Space” which is the subject of the last of 37 interweaving chapters.

That chapter dedicated to Edward Steichen‘s The Family of Man show, still the best attended (9 million), most discussed and contentious in the history of the medium, provided a benchmark for me in evaluating this book, standing as it does after chapters on the rise of modernism in photography and its use in commercial and trade displays — such is the wide-angle scope of this book, which expands the reader’s concept of what constitutes an exhibition.

The treatment proved very balanced, but Palmer and Jolly present Australian insights; the influence of Steichen’s authorial curation in Australian photography through the admiration it inspired in Hal Missingham and the aspirations of John Williams, one of the founders with Paul Cox and Ingeborg Tyssen of The Photographers Gallery in Prahran (Chapter; “Independent Photography Galleries (1970s”)) who admitted that; “The Family of Man set me off, and I’ve been trying ever since. Trying to become a photographer, and not just someone who take[s] photographs;” and influence on the interactive hanging arrangements and projections of Group M’s Photovision documentary exhibitions in the following chapter with “images of various sizes hung at various heights on white brick walls, as well as enlarged images suspended from the ceiling by fishing wire…slides projected to a tape-recorded commentary or mood music” which were greeted as “a ‘new art form'”. David Moore who with Laurence Le Guay, was one of only two Australians in The Familyis shown to have made repetutional capital from his inclusion.

Also balanced are the author’s efforts to be inclusive of all Australian states and territories, beginning with the colonial “expositions” in the then major states of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, and especially in the their chapter 26 “New Centres for Photography.” The Northern Territory though receives scant mention except as a subject for ethnographers and mining companies, and when Bernice Murphy for the second Perspecta in 1983, included thirty-three Instamatic photographs by indigenous painter Jimmy Bamabu with a cassette player commentary documenting daily life in Ramingining. “Exhibiting the Indigenous Revolution” traces the rise of an aboriginal photography facilitated by the availability of free TAFE education and finding for tertiary studies, and new realisations of history leading up to the 1988 Australian Bicentenary.

The NADOC Week National Aboriginal and Islander Photographers Exhibition in Sydney’s Aboriginal Artists Gallery brought together ten photographers, including Mervyn Bishop, Brenda L. Croft, Tracey Moffatt and Michael Riley, and Installation View gives us the voices of these artists, especially those of Moffatt and of activist artist Croft, outspoken in their determination to be given recognition and fair treatment after two centuries of injustice;

I became really aware how strongly I felt about Aboriginal people documenting Aboriginal happenings. I get angry when I see non-Aboriginal people doing it … The people who really irritate me are those whose names keep constantly cropping up in every piece of documentation of Kooris, I feel like they’re parasites. It’s just another step on from the ethnographic or anthropological kind of thing. We can do it ourselves and that’s why I feel it is really important and why I’ve been tied up in all sorts of different things like media, photography, TV and that because it all sort of weaves in and out of each other, telling our own stories. That’s what was good with Inside Black Australia in that, OK, some people weren’t technically proficient but that didn’t stop them, it’s their viewpoint, it’s out viewpoint from the inside.

Welcome also, and likewise balanced, are the authors’ own voices, never scornful nor even ironic, but even-handed in successfully conveying in “vignettes,” “something more than annotations and less than fully resolved arguments, these function as brief, evocative descriptions of key episodes or themes in the history of Australian photography exhibitions”

In the interest of encouraging readers to pick up this volume, I’ve brushed over in this review a good third of the book devoted to the last 30 years, an action-packed one-sixth of the period since that first exhibition in Australia. Postmodernism necessarily requires untangling, so its multiplicity is revisited in chapters dealing with the ‘reconstructed’ exhibition, fragmentation, the ‘death’ of photography, its performance, the return of the documentary, the digital spaces, the idea of the photographer as a collector rather than producer, a reevaluation and exploitation of the material form of the analogue photograph, the photograph in public spaces, and multiplying venues and opportunities for the medium in prizes, festivals and touring international shows.

The authors sustain the ‘parallax’ analogy, as they take “a step sideways to consider Australian photography not just as a story of ‘great photographers’ and ‘great photographs’ or a succession of different styles, but as overlapping layers of engagement between publics, spaces, institutions, photographers and curators.” As they admit “…some readers will disagree with our selection and identify omissions that we could have included,” and yes, I am disappointed to find Horsham Regional Art Gallery, which rivals Albury in its specialisation in photography, not included. Such sins of omission are forgiveable; when the angle of view here is panoramic, some parts of the scene will be occluded.

In its physical form, Installation View appears so tightly crammed with information as to cramp its thin margins. A durable hardback, the sewn binding looks to be able to withstand the frequent consultations I expect mine will endure. Alas, there is no index, an oversight, I am informed, that was precipitated by the complication of working remotely on the book during COVID lockdowns. An index though would be hard to use in the present edition given the eccentric page-numbering in (ugly) Courier typeface, for two pages at a time, tucked against the gutter at the top of right-hand pages, and none on picture spreads, where the only guides are the illustration numbers at the bottom of those pages. A separate Appendix containing picture captions and credits can be taken out to assist in identifying the illustrations, but on most pages there is ample room to have included the caption in situ, and to lose the insert means the hard-won picture records will become anonymous. Mine certainly won’t be lost given that it also includes acknowledgments amongst which is onthisdateinphotography.com!

This is a book one hopes will be reissued in a much larger format, once the 1,000 in this edition sell out as they quickly will, and on paper that better serves rare images uncovered in Palmer’s and Jolly’s research that is of such high historical value [wherever I could, for this post, I have gone back to the source for copies of the illustrations, and you will identify those copied from the book].

Thanks James, another great article, fascinating topic I never ever thought of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to read another person’s reactions to this important book James. You didn’t have my 1200 words limit to cope with but I was interested that, like me, you still had to “brush over” some parts of the book. It clearly demonstrates just how much wonderful information it contains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for taking the time to give us this review James.

From your review I believe the research and concept was excellent but the end result seems lacking. No index and paper that does not give due cred to imagery would annoy me.

LikeLike

This limited edition hardbound book is one I definitely recommend as worth having; it’s an enormous feat of research, accurate, comprehensive — a fascinating reference book that is easy to read at a few sittings, which is rare.

The titles and credits for the pictures and their page numbers are all there, but my complaint is that they are on an insert that I guess one could glue in place so it doesn’t get lost.

There’s a reason for convention in book layout – having page numbers on the outside top or bottom of each page just works. It might be less creative, but it works better than having them way down in the gutter. The Courier font I just find ugly…fine on a manuscript but not in a finished product.

Those are minor distractions from the excellent content.

LikeLike

Hi James – I agree the book design is a problem and that it is a researchers nightmare – Tho, I believe that the missing index will be released later this year…

LikeLike

Good to hear. That will reduce the hunting…the book is a great service to those interested in Australian photography!

LikeLike