May 24: For us, in this pandemic, the past returns pictures of health.

May 24: For us, in this pandemic, the past returns pictures of health.

Until 26 September, FOTOHOF archive, Sparkassenstraße 2/5020, Salzburg, Austria is showing (virtually, until it can open its doors) previously un-exhibited work of the extraordinary British-Austrian photographer Edith Tudor-Hart, from her Moving and Growing, of 1952. It provides an example for us now of a photographer more politically committed than most of us would ever dare to be.

The wellspring of her radicalism was no doubt her father, the socialist bookseller Wilhelm Suschitzky who, with his brother Philipp, ran a book store in Vienna. Jewish by birth, and known in Austrian photohistory by her maiden name, she and her family were never religious, and she was an atheist. Her younger brother was the cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky.

Her recurring photographic themes were unemployment and homelessness and particularly their effect on children; as a 10-year-old herself, after WW1 she was sent to a Swedish children’s retreat for health reasons, and at 16 she trained in Montessori teaching and went to England for an internship in 1925.

Security files record that she had joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and Russian Intelligence Service (RIS) in 1927 and behind the defiantly conspicuous codename EDITH, she remained associated thereafter. Returning to Vienna, she became close friends with the communist agent Arnold Deutsch, but at that point followed her artistic inclinations when in 1928 she began studying art, first at the Vienna Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt, then at the Bauhaus in the preliminary course with photographer Walter Peterhans [though he was de facto lecturer in the medium, there was never a photography course at the modernist school.]

It is quite apparent from images like the above that this principled documentarian would have found little of interest in formalist abstraction, beyond the emphatic ‘Dutch-tilt’ she sometimes used (below); she discontinued her studies for a sojourn in England and in 1931 published an article about the Bauhaus in the English magazine Commercial Art.

But her stay was cut short in in January 1931 with her expulsion after the Special Branch of the London Police had noted her presence at a protest in Trafalgar Square and registered her connection to the Communist Party. Her letters home to her fiancé, the English medical student and Communist Alexander Tudor-Hart, were censored or undelivered.

She produced photo essays What does the new kindergarten want? on Montessori pedagogy, and a grim take on the state of the British economy, The Market of Naked Misery (1931), made at the Caledonian Market (also photographed by fellow exiles Bill Brandt and László Moholy-Nagy) in Der Kuckuck, and was published in the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (AIZ) and Die Bühne.

She then worked for the RIS in Austria and Italy in 1932-1933, her photographic studio became her ‘cover’ (though she depended on it for income) and the Comintern promoted her as a photographer for the Soviet news agency TASS. She played a role in talent-spotting Kim Philby to the RIS in Vienna in 1933 through her friendship with his first wife, and was interrogated by MI5 about him in 1952.

Following the prohibition of the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) by the Dollfüss regime on May 26, 1933, she was arrested as an agent, and photographic material confiscated as evidence was ‘lost’. In August she married Tudor-Hart and was able to emigrate from Austria in October. Her father, fearful over the rise of fascism, committed suicide in Vienna in 1934, while her brother, also Communist, fled to the Netherlands and joined her in England in 1935.

There, Alex Tudor-Hart found work as a doctor in the Rhondda Valley in Wales and she began to document the impact of economic hardship in many small towns and villages where nine out of ten men were unemployed. To make the image below, Tudor-Hart has perched precariously on a rain-slicked fencepost, to the amusement of the miners striking against the government’s further cuts and means-testing of the dole which drew strongly attended and widespread protests like this seemingly endless procession.

In 1935 her work was included in the Artists’ International Association (AIA) exhibition, Artists against Fascism and Against War. She saw the camera as a political weapon;

“In the hands of the person who uses it with feeling and imagination, the camera becomes very much more than the means of earning a living, it becomes a vital factor in recording and influencing the life of the people and in promoting human understanding.”

On top of her martyrdom to her radical political beliefs, Edith suffered personal setbacks; her son Thomas, born in 1936, suffered from autism and her husband’s return from the Spanish Civil War ended in the breakup of their marriage. By 1947, Thomas had been placed in psychiatric institutions, never to be released. Nevertheless, she continued to expose the injustices of the era and her photographs continued to be published in Picture Post, Daily Chronicle and Lilliput Magazine.

In 1938 her name was on receipts for a Leica camera used by agents to photograph documents stolen from Woolwich Arsenal and in 1938-1939 Guy Burgess used her as a courier in contacting RIS in Paris. Her espionage activities, never fully explained, are the subject of her nephew Peter Stephan Jungk‘s The Dark Rooms of Edith Tudor-Hart (2015), made into the 1½ hr. documentary Tracking Edith (2016).

However, prior to interrogations in 1954 and fearing further prosecution, she destroyed many prints, and documents including her catalogue of negatives. Security services harassed her until her death in 1973 though could prove little. Her left-wing associations and blacklisting as a communist and a suspected traitor made work scarce until in the 1950s she gave up photography altogether and survived on income from running a little antique and book shop in Brighton.

Before she did so she left us this extraordinarily hopeful and life-affirming work which is the subject of the Fotohof show. Childhood development and photographing children was always an interest, and a side-line in child-portraiture helped sustain her meagre living.

In 1950 she was commissioned by the British Ministry of Education to take a series for a two-volume introductory work on early education Moving and Growing (London 1952). The project entailed visits to several schools and boarding schools in the wider area of London and photographing the students there during sporting activities, dance and movement exercises. In effect, the series combines her interest in child welfare and her socially committed photo-documentation.

My memories of such activities as a prep-school child in London in 1955 are coloured by an embarrassment; in my first class, instead of stripping down to my trunks, I took off all my clothes; I had it politely pointed out to me that such extremes were not necessary. Perhaps I was inspired by the sense that we were about to indulge in something very liberating, and that feeling explodes from these powerful images that make Henri Matisse‘s La Danse (1910) look rather tame.

The wan sunshine gives Tudor-Hart’s Rollieflex sufficient speed to capture the movement of these ecstatic figures with just a slight blur, and with the camera placed on the grass, the waist-level reflex provides them with a sky backdrop along the horizon of which we can see across fields the row houses from which the children come. I can still recall, as my 4-year-old self, the dauntingly high wooden rungs of the frame in the school gymnasium on which we climbed. Tudor-Hart seems to be an invisible presence as she captures such activities.

Fotohof reproduces the entire original negative area in their prints for the show, several of them still scribed with crop lines in ink from their preparation for the book.

The result is that we are given insight into her manner of working with her twin-lens camera, again often from a low angle. She eschews the use of flash, no doubt conscious of the disturbance that would cause, and lights the scene with gangs of studio photo-floods, on lightweight (but still awkward) collapsible stands, despite their intrusion into the frame in the midst of the subjects’ action. They boost the illumination to the level of the overcast day-lit scenes outside the windows and enable her to arrest moment with some expressive blur. No doubt her subjects were grateful for the heat of the 500W globes!

Her delight in directional, off-camera artificial light dates well back in her career.

What is especially striking in numbers of the images in the show is the level of physical daring involved for the children in some of the exercises and activities — joining a conga-line traversing a high sea-wall, or climbing ropes strung quite high over an asphalt playground — which in our protective and risk-averse times would horrify parents.

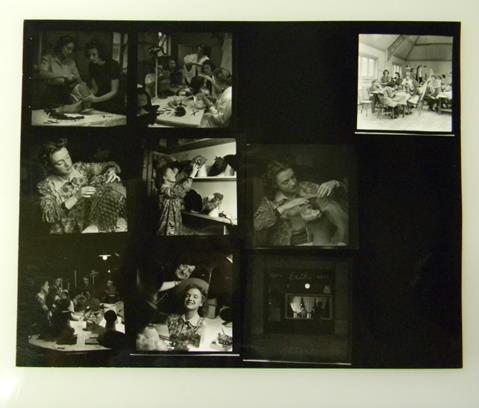

Also shown are images from two other smaller seres; the “Wartime Nursery Guildford in Somersham” (1941), one of the first childcare facilities to be set up in several English cities during the Second World War, and “Bromley Art School” (1952) near London where she made a series on the millinery class, with seven of her pictures published in Picture Post on 9 December 1944 as ‘A Girl Learns to Make a Hat’ is a photographic essay with photographs taken by Edith Tudor-Hart.

Tudor-Hart’s proof sheets reveal that no shot is wasted; driven no doubt by wartime austerity, and a consequent reliance on carefully posing the shots, yet they seem spontaneous despite being lit with her trusty photo-floods (no flash) in every case, resulting in some widely varying exposures, all fortunately ‘rescued’ through her expert printing, except in one case, the full-spread image which she has wisely re-shot upon sensing that she’d underexposed. All were then able to cropped more tightly from the square-format negatives by the picture editor — she has left room so any serves either as a vertical or horizontal as the layout demands. Her empathetic approach is learned from her European experience amongst the aesthetically more advanced AIZ and Die Bühne photographers and quite distinct from the more staid and stilted imagery of British Post staff. How many of today’s photographers could shoot this whole series on two rolls?

Tudor-Hart has determinedly approached the assignment with a mission to cover the subject and her assertiveness in getting everything needed for a successful narrative is apparent on the proofs. The magazine editors however, chose not to use the image she might have intended to close the essay.

From out of a miserable fate Edith Tudor-Hart nevertheless stirs our joy in memories of those moments of childish freedom and delight in life and vital health.

Her negatives are part of the estate that the Suschitzky family handed over to the FOTOHOF archive and from which they produced these exhibition pictures. You can make a virtual visit to the exhibition yourself and the individual photographs can be found in the archive.

What a terrific piece James, and the photography is stunning, I’ve never seen any of it before, thank you, I really appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, extraordinary work deserving the exposure it is now getting.

LikeLike

Dear Dr McCardle,

I am researching the photojournalism of Robert D. (Tom) Hutchins (1921-2007) whose essay on China in 1956 was published by Life magazine in January 1957, and can’t find any reference to how much Life paid him. He went to China as a freelancer with the understanding that Life might bankroll his trip if they published his work, but I can’t find any reference to the kind of money the magazine paid out or an essay by a stringer going where their photographers could not?

I really admire your writing on the histories of photography and tried to alert you to the book Photoforum at 40…. Nina Seja’s history of our New Zealand organisation, because like Australia, we were also influenced by Bill Jay and Sue Davies etc in the early 1970s. I don’t know if you have seen my Photoshelter website (see link below), but I now have around 1,500 of Tom Hutchins’s China 1956 images on it.

I hope you can help with this query. Tom and David Moore were friendly acquantances, also.

Kind Regards,

John Turner johnbturner2009@gmail.com http://www.jbt.photoshelter.com

LikeLike

Fascinating article James

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing this. Very impressive photos. Great range of topics and styles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear James Mcradle,

thank you for this very excellent text on Edith Tudor-Hart. It contains much more valuable information on her work than we had, when we put on her show at FOTOHOF archiv. It should be a must for our visitors to read your text before they come to see the pictures. By the way, now not only the virtual exhibition can be visited, also the gallery is open again for visitors. We would be delighted to welcome you in Salzburg, but we are equal happy to read your excellent article. May we link it on our website? Best greetings,

Kurt Kaindl, co-curator Edith Tudor-Hart, Fotohof

LikeLike

Dear Kurt, thank you for your kind comments. Certainly, do link to the article from your website, quote from it or print it…all my articles are Creative Commons licensed Attribution CC BY. Wonderful to know that the gallery is open once again! I wish I could visit, but the virtual visit you have arranged is a helpful substitute. With much appreciation for your work in promoting gratitude photography; I’ll keep an eye out for your upcoming shows.

LikeLike

Glad I was able to read the article you linked to from Academia.edu …

And that is so cool that an archivist above is here.

Love Tudor-Hart’s work from 1941-52.

And the points about abstraction and tilts and photographic technique.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you could make it! Thank you for your comments; good to know another admirer of Tudor-Hart…may she become even better known!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I came upon this wonderful piece about my Aunt Edith by chance. Thank you so much for posting it. So good to see her images – what a wonderful photographer she was!

LikeLike

..and what a remarkable person who lived a life well out of the ordinary. I’d love to find out more about her, as a person, from you. Also, how accurate on her later years is the Wikipedia entry on her? Thank you for taking time to make contact here. James

LikeLike

Belatedly, thank you for your reply.

If you would like to contact me by email you are welcome. I would like to help in any way I can. Julia

LikeLike