February 22: The camera is a one-eyed cyclops, but what of the one-eyed photographer?

February 22: The camera is a one-eyed cyclops, but what of the one-eyed photographer?

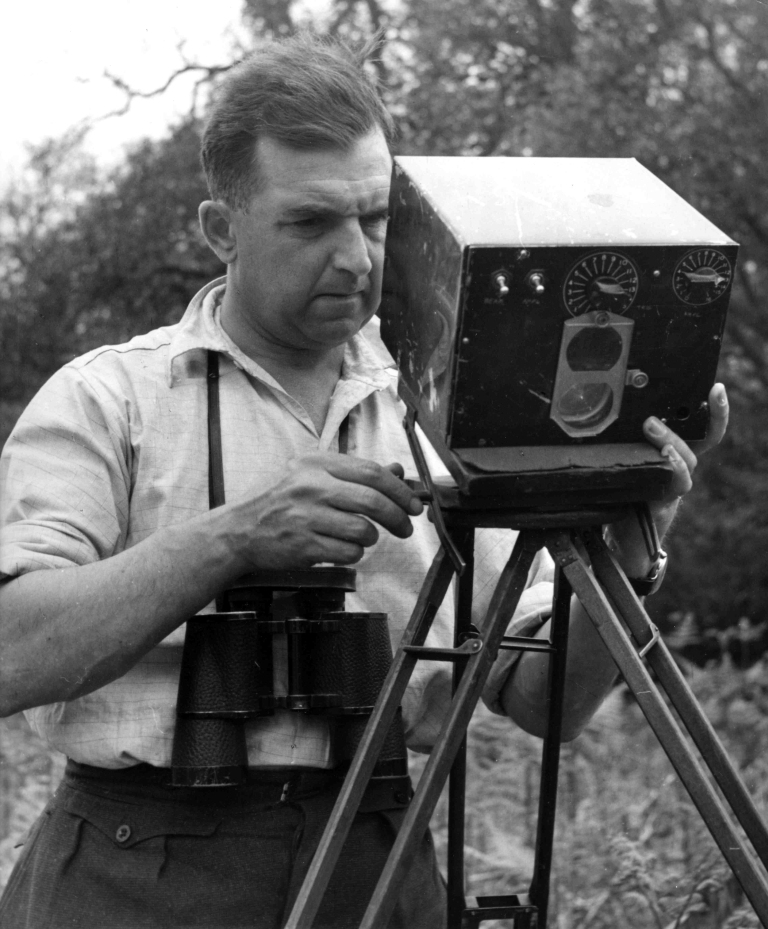

Today marks the death of Eric Hosking in 1991 whose success, resulting in his work appearing in around 800 books, was achieved by accident, or more accurately, through an accident.

A keen amateur naturalist as a Cockney child in straitened circumstances, he kept his collection in matchboxes, and these receptacles were soon replaced by the expedient of using a five-shilling box camera with which to preserve his treasures as images. He then purchased for 30 shillings, from a stall in London’s old Farringdon Street market, a 1909 mahogany quarter-plate Sanderson field camera with an f8 lens and bellows.

At 15 Hosking had left school and was apprenticed in the motor car industry until, in 1929, his firm went into liquidation. In the meantime with glass plates provided by his parents he pursued his passion for photographing birds. During the breeding season in Staverton Park, 4 hours away by train from home and near Woodbridge in Suffolk, he photographed bullfinches and other species at the nest, and there, hearing nightingales singing in quartet on a warm May night, he found himself in tears, such was his delight.

He was on the dole at the start of the Great Depression and in the most depressing period of his life, but by luck, an old school friend, then a sub-editor on the Sunday Dispatch, asked Hosking to go to London Zoo and photograph the six-month old elephant seal. He took the 4 ½ year old daughter of a friend to provide a sense of scale, and for his effort he received two guineas. Buoyed by his success he repeated the exercise with a variety of animals. Armed with this folio one morning early in 1932, with no appointment, he went to see the editor of The Times, Geoffrey Dawson (1874–1944), who obligingly invited Hosking for a cup of coffee in a nearby teashop to look through the pictures. He recommended Hosking to the editor of the Daily Mirror; its February 2, 1932 centre-spread featured four of Hosking ‘s photographs. He went on photographing animals and children together to earn all of £23 that year (worth about £1,500 now). In 1933 Oxford University Press published a book of his pictures called Friends of the Zoo which ran to three editions.

Nevertheless, Hosking had to support himself with child portraits and weddings, and it was 1937 before wildlife pictures really began to provide him with a satisfactory income, and only because of publicity very costly to him. He had constructed a 7-metre-high hide close to the nest hole of a pair of tawny owls. On 13 May 1937 as he climbed in utter darkness to undo the fastening at the rear of the hide, one of the owls attacked him, its claw sinking into his left eye. Rushed to hospital in London, it was feared that unless the eye was removed, infection might blind him completely. The surgeon having given him just 24 hours to decide what to do, Hosking’s minister came to see him and mentioned that Walter Higham (1900–1972) had lost an eye in a shooting accident at seventeen but had gone on to be a successful bird photographer in his mid-twenties.

Knowing this helped the 27-year-old Eric to decide and the doctors removed the eye next day. Only the night after being discharged, and harbouring no hard feelings, Hosking was back at his hide in Wales wearing a fencing mask for protection, only to find the young owls had flown. Nevertheless, the accident with the owl brought Hosking publicity; the day after the operation the story was in every national newspaper, and his photographs were in great demand. Unexpectedly he found himself becoming a popular public lecturer, providing the fare for more than 200 illustrated talks in church and town halls during that winter of 1937-38.

It’s is the stuff of legend, and the reality of his success was only achieved through hard work, Hosking’s perfectionism and his charming personality.

“Eric Hosking is a bird photographer and he is ever careful to keep his priorities right: the bird comes first. He is hurt if he thinks any action of his has caused a bird distress,”

…so wrote Frank Lane, frequently Hosking’s co-author on his several books, and his estimation is borne out in the photographer’s distaste for others who ‘gardened’ a site in order to expose the nest, and for fear of causing birds to desert their nests, he would always keep hides at a distance, and painstakingly tie back an intruding branch rather than cut it off. He innovated in order to get the sharpest and best-lit results of birds engaged in characteristic actions and in their habitat. Flash bulbs and then electronic flash enabled him to freeze flapping wings and darting motion.

Though until 1947 he continued to use his old Sanderson for all his serious bird pictures, in order to overcome the slowness of human reaction times compared to avian, he switched to 35mm, a format then despised by ornithologist photographers, but which he used almost exclusively after 1963; he first used the Leica rangefinder in 1935 then settled on the Olympus OM2 reflex from 1974, sometimes also using a Hasselblad. When Kodachrome became affordable he quickly took up colour photography, which enhanced the attractiveness of his books.

Still finding his reaction times far too slow he commissioned scientist Philip Henry to make him an electronic sensor which would automatically release the shutter to photograph birds in flight in the exact plane of focus. The double meaning of the title of Hosking’s autobiography An Eye for a Bird while ironic, is not sardonic; his genuine affection for birds shines through. However, some of his claims are hyperbole; that he initiated the use of pylons for bird photography in 1936 cannot stand up against the fact that Dr. Francis Hobart Herrick had built towers to photograph nesting Bald Eagles along the south shores of Lake Erie, as early as the 1920s; and his claim to be the first professional to make a living from bird photography overlooks the brothers Cherry and Richard Kearton working as early as the 1890s.

The competitive streak that runs through bird photography, as it does amongst the ‘twitchers’ themselves, probably accounts for his self-aggrandisement, but it has brought rapid advances, encouraged in some measure by Hosking’s judging of the early Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards, and since his death through the Hosking Charitable Trust that supports wildlife projects across all media, and the use of his name in the Eric Hosking Portfolio Award by the British Natural History Museum.

Bird photography has become a specialised genre, a highly developed art with its own stylistic characteristics and aesthetics in service of accuracy record-making, but not itself ‘Art’. Rather, ‘shooting’ birds is an extension of the idea of collecting specimens that we might associate with the work of Syms Covington in Roger McDonald’s popular historical novel Mr. Darwin’s Shooter, which at the same time serves scientific and documentary purposes.

Consequently, where photographs of birds appear as art, this is a universally recognised genre that can be critically deconstructed for a variety of purposes.

Finnish artist Sanna Kannisto (*1974) makes photographs of birds, and plants associated with them, against white backgrounds so pristine that we mistake them for the illustrations of the many ‘bird books’ we use to identify them. Photographs are rarely satisfactory as a visual index to the attributes of particular species and therefore are usually substituted with tinted drawings assembled from numbers of photographs for the most ‘typical’ example. Such a double-take, on viewing her shots of real birds with taxonomic titles, is encouraged by her use of a backlit semi-translucent white opal acrylic sheet that she sets up behind a branch before waiting for a bird to alight upon it.

“Being with a bird is utterly unique. It is moving. The gaze of a bird is mysterious. I look at the bird and it looks at me. For a moment we have some kind of shared thought. It’s a kind of mutual examination.”

We are given to understand that these images, that rely on preparation, chance and patience, share at the same time the characteristics and tropes of studio fashion photography; the white background and the perfectionism that arranges every detail and which exalts the status of the common model.

“Nature is total, uncontrolled and on the other hand perfect.”

Had this onthisdateinphotography entry been made a year ago, I would have included mention of Jochen Lempert and Peter Piller‘s Reconsidering Photography: Birds at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, 20099 Hamburg, held 27 October 2017 until 4 February 2018. Piller (*1968) had a juvenile fascination with bird-watching that he found he shared briefly with his pre-adolescent son, and has since continued to take bird photos, some of which have entered his art practice which extends across a range of media and mischievously overturns our norms. His exhibition of these images at Barbara Wien gallery, Schöneberger Ufer 65, 10785 Berlin, 25 Nov 2017 – 17 Feb 2018, was called behind time, and aptly so, because his bird pictures all represent his apparent failure to press the shutter at the right moment.

He titles the above A bird photographed on Heligoland that I cannot identify. The location is the island of Heligoland in a small archipelago in the North Sea, made important in ornithology and studies of bird migration by Heinrich Gätke’s 1890 book Heligoland, an Ornithological Observatory. Piller’s unidentified bird exits the frame and we are left with its unsatisfactory near absence and only fleeting evidence of it, and that is for what Piller selects it;

“…the birds are fleeing from being photographed and the image and from myself, because I only disturb them with my presence.”

No doubt Eric Hosking discarded many such images, but they are of value to Piller who, alongside the bird photographs, showed new images on hotel and university letter paper “drawn without imagining something first”, with a text written over the drawing and developed in parallel, as a representation of the “borderline between the inner and outer world”. During their making, he says:

“I ask myself as often as possible: why am I even doing that and what’s that point? Mostly I tear up pages the entire day, because the whole thing is not working or I’m waiting, like with the bird photography when you’re ready for hours and nothing is happening, in pleasant complicity with the failure, the uselessness and the waste of time. I like the discipline that comes with being ready for an idea much more than conceiving something. I desire most the possibility of surprising myself.”

In other words, photographing birds is a means of observing not birds, but his consciousness and desire. Is that an unacknowledged part of all bird photography, and the part in which art exists?

Wonderful post James… I really enjoyed your insights. The last para denouement – great stuff!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Marcus – much appreciated!

LikeLike

Lovely post

LikeLike

Thank you Sharon, much appreciated!

LikeLike