October 24: On this date in 1905 a woman submitted a US patent for an improved colour process

October 24: On this date in 1905 a woman submitted a US patent for an improved colour process

“If we could devise some simple process for making colour photographs, it might have quite a vogue”, mused George Eastman (1854–1932) somewhat prophetically in 1904. An unsung woman inventor, Florence M. Warner (1880–1940) had an answer.

Eastman had been a major motivator behind improvements and advances and popularisation of photography and now felt colour was within reach, though in 1904 he was ignorant about developments in colour photography then taking place in various parts of the world. By 1911, when invited to talk about colour photography he knew enough to be able to engage an audience with his account of its progress, citing James Clerk-Maxwell (1831–79) for his 1861 additive superimposed projections of positives from negatives shot through colour filters. Ducos du Hauron (1837–1920) patented a subtractve process in which unwanted colours are absorbed, but it was difficult to put into production. The Lumiere Brothers’ process dyed starch grains in three colours, sifted them onto glass plates, flattening the grains and filling in the gaps between with lamp black to produce a soft, grainy but beautiful image which was to be marketed from 1907 as the Autochrome. In the meantime there was urgent investigation being done by Eastman’s German competitors Agfa and Rotograph, Clare L. Finlay (†1937) in England, and du Hauron in France.

Du Hauron described a trichromatic method which instead of being carried out on three separate plates, was to be combined in one plate by means of a trichromatic screen divided into narrow juxtaposed lines or minute spaces, corresponding to the three primary colours, red, green and blue-violet, so that the transparent colour of each of these lines or spaces acted as a colour filter.

A sensitive panchromatic plate exposed in contact with this screen was to produce a negative with lines or spots corresponding to the relative strength of the three colours passing through it. A diapositive print on glass subsequently registered with the tricolour screen would show the object in its proper colours. HIs method remained impractical while panchromatic material, sensitive to all the colours to be used, remained unavailable.

Between 1892 and 1898 several patents were taken out by James W. McDonough and Liloly for various methods of preparing the trichromatic ruled screens envisaged by du Houron, with fair success, but disadvantaged by the coarseness of the lines and the need for two screens, one for taking and another for viewing, which made the method too costly.

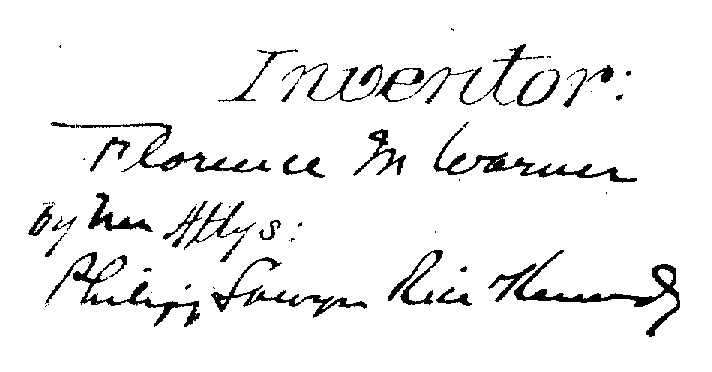

Miss Florence M. Warner had patented her “Florence” chromatic plate in 1905 in partnership with J. H. Powrie. It is strange she is so little known today, and almost no biographical detail about her exists apart from Eastman’s record in his biography. Her patent was an improvement on the LiIoly method. In this case the colour screen was photographically printed on a glass plate, coated with panchromatic emulsion and exposed to the coloured object through the screen.

The Warner-Powrie process was the earliest commercial process using a screen made with bichromated colloid. A glass plate was thinly coated with bichromated gelatin or fish glue and exposed to light through a screen having opaque lines twice the width of the spaces between. The nonexposed portions ofthe colloid were then washed away, leaving the hardened lines which were dyed, say green, and then mordanted. The plate was again coated and exposed a second time with a screen moved to cover up the lines formed during the first exposure. Following a second washing the new lines were dyed red and mordanted. The same procedure was repeated a third time except that the exposures were made through the back of the plate with a blue filter, and without the use of the screen. (as described in Mees and Pledge, 1910, pp. 200-201)

They got good results. Eastman invited them to come from Chicago to demonstrate their process. Warner’s process seemed to Eastman to be both cheaper and of better definition than any others which he had seen; he described them as “beautiful when thrown on a screen by magic lantern.” However exposure times and the need for a second camera to produce positives from the negatives was not the easy solution he sought for marketing to the average consumer. He admitted the colour was rich and beautiful but only when the most powerful arc lamps were employed to project the image. However Eastman devoted Frank Lovejoy and John Huiskamp to develop the Warner/Powrie project.

Warner and Powrie toiled at their invention at Kodak Park but experienced difficulties in getting uniform results, so that Eastman did not exercise his option. Condescendingly he reports that “Miss Warner sailed out in a huff”, but she was mollified when he told here he had not lost interest. An inventor, if she was a woman, faced male attitudes that a man was entitled to rebuff or negotiate where she was regarded as ’emotional’, to be pacified.

Warner and Powrie published articles about their discovery, including Powrie, J. H. The origin of the Warner-Powrie process and application of the Florence plate to process work in Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, 1905-1906, p. III, and 1907-8, pp. 9-16. She received further attention from the British Journal of Photography in issues of Oct 4 1907, Nov 5 1908 and June 4 1909. Each of the BJP articles recognises and speaks well for the Warner/Powrie attributes of vividness of colour and of finesse of detail which they rated above other processes.

Warner and Powrie published articles about their discovery, including Powrie, J. H. The origin of the Warner-Powrie process and application of the Florence plate to process work in Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, 1905-1906, p. III, and 1907-8, pp. 9-16. She received further attention from the British Journal of Photography in issues of Oct 4 1907, Nov 5 1908 and June 4 1909. Each of the BJP articles recognises and speaks well for the Warner/Powrie attributes of vividness of colour and of finesse of detail which they rated above other processes.

The partners corresponded also with Thomas Edison over the period 1909-1915 dealing with their experiments in colour motion picture film using their process. Most of the correspondence is between Frank L. Dyer of the Legal Department and patent holders John H. Powrie and Florence M. Warner. There are also letters to and from Edison, along with other items bearing his marginal notes. Letters from and about Willard C. Greene, a photographic experimenter in Edison’s West Orange laboratory show he considered Warner-Powrie film impractical for Edison’s kinetoscope. Other items relate to the products of the Lumière Co., including autochrome and panchromatic plates, and to consultations with Pathé Frères. A letter by engineer Charles Bardy to Florence regards emulsification machines. It is clear that her work was regarded as a genuine prospect.

Powrie did, indeed, patent a line screen motion picture product in 1926 and demonstrate it in 1928, but little record is left of Florence’s activities after her second patent for a further process, refined no doubt thorough the development for Eastman and Edison, was lodged by her in 1920.

She deserves better.

4 thoughts on “October 24: Trichromatic”