January 23: Photography is a way to access the extraordinary, to “put the marvellous in your pocket.”

January 23: Photography is a way to access the extraordinary, to “put the marvellous in your pocket.”

Canadian art history would register Alix Cléo Roubaud, who wrote the above, as a minor figure of that country where she was born Alix Cléo Blanchette on this date in 1952. She lived in France from 1972 until her death.

During her life Roubaud’s work was only really known to those closest to her. In 1982, the year before she died at 31, she approached a number of Parisian galleries but they had no interest in her work.

French filmmaker Jean Eustache, made a 15-minute documentary Les Photos d’Alix (1981) about his friend, but it was not until after her death in 1983 that her photography was exhibited publicly. She remained marginal and elusive until in 1984 her husband, French writer Jacques Roubaud, was able to have part of her journal publish by Editions du Seuil.

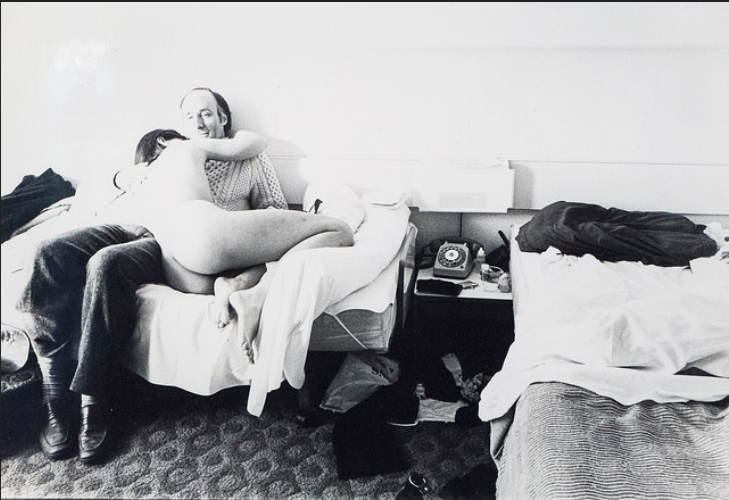

The published dairy of Alix Roubaud covers 1979-1983, and is a chaotic and rambling, fragmented but affecting text, and it contains some of her pictures when up to that point, apart from those shown in Eustache’s film, there were none available. They illuminate her strange photographic practice revealing that her aspiration was to use the medium to “liberate the soul of things. Their immaterial double.” Her picture of Eustache, above, exemplifies her approach in portraiture; a double profile in which upon our closer examination we find ourselves staring into the intense but sympathetic eyes of the filmmaker.

When in 2009, Editions du Seuil republished the journal, an introduction by her husband was included that provides some biographical context, and the update also includes additional reproductions including her entire photographic series Si quelque chose noir. The revised publication brought a renewed interest in her work amongst French speakers which broadened when Dalkey Archive brought out an English edition the following year. More recently, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France held a survey exhibition Quinze minutes la nuit au rythme de la respiration 28 October 2014 to 1 February 2015.

In a sense the diary addresses husband Jacques Roubaud and many of the photographs partake in their intimacy; not only are these self-portraits but they are of herself as one part of the couple. His release of the diary recognises her editing and retyping of passages of her journal into the diary, but is also a kind of reply to her.

Her husband’s introduction explains how she came to photography:

Born in Mexico (her father, Arthur Blanchette, a diplomat; her mother, Marcelle Blanchette, a painter), Alix was Canadian and bilingual. Alix’s Journal is written in French (mostly) and English. Nomadic during her childhood and adolescence (living in South Africa, Egypt, Portugal, and Greece), she had retained the sense from these wanderings of not spontaneously possessing either of her two languages (French, her maternal language, and English, her paternal language), which she spoke and wrote interchangeably, having in each an invisible accent stemming from no particular region. She gave the impression of being, in each, “always translating.”

She completed her secondary schooling in French lycées: she derived her love for the sun from Athens; in those years, she had hardly suffered from her asthma, and she associated the joy of sunlight with that of breathing effortlessly, freely[…]that same moment in August 1978 also marked Alix’s discovery of photography. It happened in the infinitely serene solitude (this is how she experienced her stay) of a small spa town in the mountains (but medium-sized mountains, not near the Alps or the Pyrenees) popular with spa-goers of limited means in the centre of France―incredibly atypical for her, who was touching and at the same time absurd with all her old-fashioned manners and obsessions.

The 2014/15 BnF exhibition took its title from a 1980 print, made not long after Alix Roubuad’s 1978 discovery of the medium described above (and perhaps was actually made at the spa; 1980 is the date of the print). A blurred image, it is striking when one reads the title which explains the process used; standing, clutching the camera to her chest in the night for fifteen minutes, with open shutter she has recorded not the landscape, which is a mere vestige, but the experience of it and of her own breath, which has caused the motion and repetition.

The bleeding of the blacks is an effect she repeats artificially in printing of other images; an effect which makes ‘quelque chose noir’ (title of her series Si quelque chose noir) out of otherwise ‘straight’ images.

This is achieved by using a torch masked off to a pinhole size, literally a pinceau lumineux (a ‘light-brush’) to create the streaks.

Both images depict the moustachioed man in the hat above (solely in briefs for the image below), who appears, laughing with another woman, standing next to the photographer who is nude from the waist down. In both ‘holding-back’ (masking) in the printing obliterates the electrical conduits and other detail in the room, reserving white for the light-brushing.

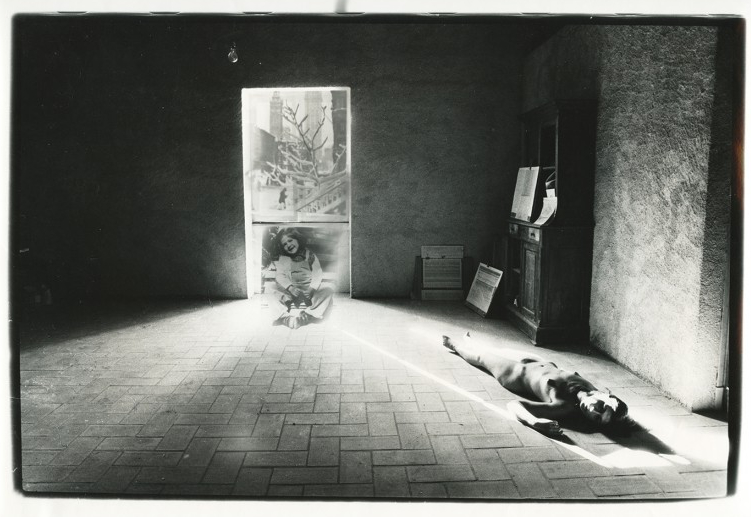

The most extraordinary of her print manipulations is in her series Si quelque chose noir, made at Saint-Félix in 1980. In this frame from the sequence she appears twice; once as a laughing, crosslegged child, an appropriation from a family snapshot, superimposed by double-printing into lighter tones reserved by the floor-length window; and as her own corpse. The little girl then is represented as laughing at her own death, which is a particularly macabre evocation of the way the photograph compresses and concusses time. In another picture from the series taken in the same stark brick-paved room Roubaud makes it appear that she casts no shadow.

Alix Roubaud struggled with alchohol, smoking, drugs, depression and suicidal thoughts, and in fact attempted suicide several times before she died of a pulmonary embolism. Several of her images are deliberately made ugly by these impulses and obsessions, as in the series Alcohol: Homage to Morris Louis in which painting with photo-chemistry and solarisation obliterate much of the image or extend it in a painterly form as in this print in which a wine glass nestles amongst a maelstrom of twisted sheets with half-smoked cigarettes and a razor blade which itself is highlighted menacingly in a nicotine yellow. The miasmatic forms created by Roubaud’s mistreatment of the print drain the sunlight from it.

The insomniac Roubaud writes in her journal for “4.1.80,2 A.M.” (p. 28):

Jacques asked me to jot down a phrase I had uttered during a conversation with him in the middle of a Wednesday: the photograph of a loved one, however close and familiar that loved one may be, in itself restores the love from a distance: the primal intangibility and strangeness, always fascinating, of a face one has not seen.

The blurb for the Dalkey Archives English edition of her Diary announces, “In 1983 Jacques Roubaud’s wife Alix Cleo died at the age of 31 of a pulmonary embolism. The grief-stricken author responded with one brief poem (Nothing), then fell silent for thirty months.”

He seems to respond to her diary entry above with I Can Face Your Picture in Some Thing Black (Jacques Roubaud, translated by Rosmarie Waldrop, also Dalkey Archives, English edition)

I really can face your picture, your ‘likeness’ as it used to be called. it’s difficult, but I can.

Scattered among lights, among your shadows.

Enumerated place after place: walls, drawers, this book:

Images of you, these words.

Your letters.

Your writing and typing: Canadian.

Your twofold tongue. sight.

But I can’t bring myself to listen to your voice again: the cassettes you recorded, all those hours, at night, the final months.

Other traces of you, come through my other senses, are only inside me. These I stumble on and choke.

If you care to look, there is much to find in common between Roubaud and her American contemporary Francesca Woodman, who suicided the year before, though Woodman was six years younger and achieved greater recognition. Both were self-portraitists, but Roubaud was more experimental in the darkroom while Woodman created her images mostly in-camera. Each depicted themselves as spilt beings, in equal parts carnal and ethereal. Sadly, it took Roubaud’s also premature death, and longer still, to bring her to attention. Both have much to teach about the ‘selfie’!

Reblogged this on Palmer-Methode.

LikeLike